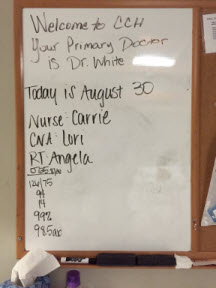

September 26, 2015. I saw Angela, the respiratory therapist, a few minutes after I arrived at the CCH at 7:35 A.M. She said that after she set up a couple of more patients, she would return to Dad’s room to continue my training. Jennifer, the charge nurse, was also tasked with training me this weekend. Her instruction started with having me administer Dad’s morning meds. We started with the pills, which I was to crush and mix with water. I then drew up the liquid mixture into a syringe and emptied it into the PEG tube. The other two meds were powders: the Renvela was for his kidneys and the Beneprotein was a nutritional supplement. According to Jennifer, I had to mix the Renvela with water and then squirt out 1/3 of the mixture into the sink. The entire sachet of Beneprotein was injected into the PEG tube. After injecting all of the meds and supplements, I flushed the tube with lukewarm water to ensure that nothing remained. So far, so good.

After Jennifer left the room, Dad asked me about “all of the buildings that he was going to travel through.” I explained to him that to get home, he wouldn’t travel through buildings, but that his ambulance would take him home via the Loop and 31st Street. I drew him a bad, oversimplified map of the area and explained where everything was and the distances between them. He had been hospitalized so long that he was confused, thinking that there was a difference between our house and our home. He then told me that it would be prudent to get him a bedpan, so I called the nurse and left his room.

After Jennifer left the room, Dad asked me about “all of the buildings that he was going to travel through.” I explained to him that to get home, he wouldn’t travel through buildings, but that his ambulance would take him home via the Loop and 31st Street. I drew him a bad, oversimplified map of the area and explained where everything was and the distances between them. He had been hospitalized so long that he was confused, thinking that there was a difference between our house and our home. He then told me that it would be prudent to get him a bedpan, so I called the nurse and left his room.

While waiting in the hallway, I encountered Dr. Smith and conferred with him for a few minutes. While we were chatting, he told me that I was pretty lucky because Jennifer was one of Scott & White’s top 25 nurses of the year. I had just met her this morning and had already concluded that she was very friendly, supportive, and professional. I also didn’t pick up any vibes that she was judging me for moving Dad to home care.

At 11:00 A.M., Angela returned, and my respiratory therapy training ratcheted up a notch. In addition to suctioning Dad today, she said that I would change out his tracheostomy tube. I had hoped to record the process with my camera, but I ran out of disk space before I was finished. Regardless of whether you were suctioning or changing out the trach, the process required a sterile environment. There was a specific way in which to open the kit and put on the gloves, which I thought would be my undoing. Putting on a pair of gloves so that you don’t touch and contaminate them was not as easy as you might think, and I felt like a complete doofus.

At 11:00 A.M., Angela returned, and my respiratory therapy training ratcheted up a notch. In addition to suctioning Dad today, she said that I would change out his tracheostomy tube. I had hoped to record the process with my camera, but I ran out of disk space before I was finished. Regardless of whether you were suctioning or changing out the trach, the process required a sterile environment. There was a specific way in which to open the kit and put on the gloves, which I thought would be my undoing. Putting on a pair of gloves so that you don’t touch and contaminate them was not as easy as you might think, and I felt like a complete doofus.

I had a tiny problem getting the trach tube into his throat, but I think it was because I didn’t insert it at the correct angle. I panicked a little; Angela took over, and it slid right in. She also showed me how to clean the trach that I had just removed and how store it for the next changeout. As if all those steps weren’t important enough, it seemed like the biggest lesson was that you had to ensure that you tightened the collar enough so that it wouldn’t come out, yet not so tight that you choked the patient. Being able to place two of my fingers between the trach collar and Dad’s neck seemed to ensure the correct fit. I was a little stressed out and I couldn’t believe that I would have to perform this procedure every seven days. Was it that long ago that I thought to myself that I couldn’t imagine having to change out a trach? Sheesh.

While I was sitting with Dad, Angela returned to the room with printed instructions about how to suction and change out a trach. Dad was sleeping, so I decided to read the entire document. I write technical documentation for a living, and although I’m not diligent about always reading it, this seemed like a good time to read the manual. I was glad that I did. When Angela stopped by again, I told her that the two other respiratory therapists had had me insert the tubing much further into Dad’s trach than the instructions advised. She told me that she had noticed that I had performed deep suctioning on Dad, but that it wasn’t necessary. When I changed my suctioning technique, I found that suctioning didn’t hurt Dad the way it did with some of the respiratory therapists. I was glad that Angela was now my trainer. I recalled how Dad had told her that she was different from the other respiratory therapists and how he didn’t like others, like Victor. Angela had me suction Dad the rest of the day, and by the end of the day, I was somewhat comfortable with the procedure, although I still had to psych myself up for it.

While I was sitting with Dad, Angela returned to the room with printed instructions about how to suction and change out a trach. Dad was sleeping, so I decided to read the entire document. I write technical documentation for a living, and although I’m not diligent about always reading it, this seemed like a good time to read the manual. I was glad that I did. When Angela stopped by again, I told her that the two other respiratory therapists had had me insert the tubing much further into Dad’s trach than the instructions advised. She told me that she had noticed that I had performed deep suctioning on Dad, but that it wasn’t necessary. When I changed my suctioning technique, I found that suctioning didn’t hurt Dad the way it did with some of the respiratory therapists. I was glad that Angela was now my trainer. I recalled how Dad had told her that she was different from the other respiratory therapists and how he didn’t like others, like Victor. Angela had me suction Dad the rest of the day, and by the end of the day, I was somewhat comfortable with the procedure, although I still had to psych myself up for it.

I was glad when it was time to go home for lunch.

After I returned to the CCH from lunch, Jennifer and I got Dad into the wheelchair. The next time that Angela came in to suction Dad, she noticed that he was slouched in the wheelchair. She said that he was too bent for suctioning and she would wait until he was back in bed and at a better angle. I made a mental note to myself that the angle of his neck was important when suctioning the trach.

I was by myself at the CCH for most of the day. Mom was at home preparing the house, especially the master bedroom, for Dad’s homecoming. Stan split his time between performing chores at the house and running endless errands.

If you spend any time at a hospital, you quickly learn that healthcare is a dirty business and the floor is difficult to keep clean. My parents’ house, including their bedroom, was carpeted with a beautiful sea green carpet. We were pretty certain that the carpeting would not survive Dad’s home care. One of Stan’s assignments was to figure out how to save the carpet. He eventually decided on chair mats. He bought out the supply of rectangular mats at Staples and Office Max and then worked out the arrangement of the mats in the bedroom. In addition to protecting the floor, the mats provided a relatively hard surface and protected the carpet from some of the heavy equipment and the wheelchair that would be brought into the room. He also purchased some shelving and boxes that we would need for storing medical supplies. Thank goodness my parents’ bedroom was large enough to accommodate everything.

If you spend any time at a hospital, you quickly learn that healthcare is a dirty business and the floor is difficult to keep clean. My parents’ house, including their bedroom, was carpeted with a beautiful sea green carpet. We were pretty certain that the carpeting would not survive Dad’s home care. One of Stan’s assignments was to figure out how to save the carpet. He eventually decided on chair mats. He bought out the supply of rectangular mats at Staples and Office Max and then worked out the arrangement of the mats in the bedroom. In addition to protecting the floor, the mats provided a relatively hard surface and protected the carpet from some of the heavy equipment and the wheelchair that would be brought into the room. He also purchased some shelving and boxes that we would need for storing medical supplies. Thank goodness my parents’ bedroom was large enough to accommodate everything.

By the time that the three of us met at home at the end of the day, we all felt like we had put in a full day’s work and were ready to make use of my parents’ bar.

September 27. I woke up at 5:30 A.M. and wandered into the kitchen to make coffee. I was surprised to find that my mother was already up and about. She told me that she had been awakened at 3:15 A.M. by a phone call from some college. The crank calls persisted until about 5:00 A.M. Before the annoying calls stopped, she had reached the point where she would answer the phone and immediately hang up. By the time that I woke up, she had done a lot of housework and was exhausted.

Mom and I arrived at the CCH at 9:00 A.M. Dad was awake and promptly told Mom that he had been trying to call her since 3:15 A.M. What Mom had heard was the audio caller ID announce wireless caller. The audio wasn’t all that clear, so you might imagine that it sounded something like Warless College, especially at 3:15 A.M. Mom might have appreciated the humor of the situation more if she had had 2-1/2 hours more sleep. My father could be a real pill with a phone. I don’t know if we ever knew why he was calling.

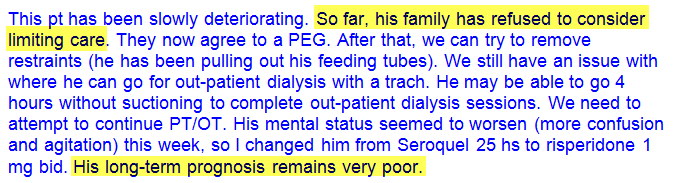

Shortly after we arrived, I went to the nurses’ station to see Jennifer. She said that she had been waiting for me to arrive so that I could administer Dad’s morning meds. At practically the same time, Dr. Smith arrived and we discussed Dad’s feeding tube and his invasive lines. I agreed with the doctor that because of its upkeep and the potential for infection, we wanted the PICC line removed. It was used to administer IV medication and he had already changed Dad’s prescriptions so that he was no longer receiving any IV drugs. Dr. Smith said that if we had an emergency, we could use the dialysis catheter while trying to start another IV or insert a new central line. He said that nephrology wouldn’t like this option, but in a pinch the dialysis catheter would work. During our discussion I learned that Dad had been tested for the Candida fungus five times and had tested positive only the first time. It sure would have been nice to know this sooner. If I had had more time to think about it, I would have resented being manipulated by Dr. Ciceri. I still shudder when I thought about how close we came to withdrawing care because of misleading information.

Shortly after we arrived, I went to the nurses’ station to see Jennifer. She said that she had been waiting for me to arrive so that I could administer Dad’s morning meds. At practically the same time, Dr. Smith arrived and we discussed Dad’s feeding tube and his invasive lines. I agreed with the doctor that because of its upkeep and the potential for infection, we wanted the PICC line removed. It was used to administer IV medication and he had already changed Dad’s prescriptions so that he was no longer receiving any IV drugs. Dr. Smith said that if we had an emergency, we could use the dialysis catheter while trying to start another IV or insert a new central line. He said that nephrology wouldn’t like this option, but in a pinch the dialysis catheter would work. During our discussion I learned that Dad had been tested for the Candida fungus five times and had tested positive only the first time. It sure would have been nice to know this sooner. If I had had more time to think about it, I would have resented being manipulated by Dr. Ciceri. I still shudder when I thought about how close we came to withdrawing care because of misleading information.

I put on a hospital gown over my Sunday clothes and administered Dad’s morning meds. Mom and I left for church at 10:20 A.M. and once again, Stan stayed and visited with Dad.

When Mom and I had attended church last week, we had a very sobering and tearful meeting with our good friends, who I referred to as the church ladies. Our friends at church had prayed their hearts out for Dad, and they were heartbroken about his prognosis. As upset as they had been last week, they were thrilled today. They and Pastor Tom praised God about the miracle that had occurred.

Stan had a good visit with Dad and left the CCH when I called him at 12:25 P.M.

I returned to the hospital at 2:00 P.M. to find that Jennifer and the aide were giving Dad a bath. When they were finished, Jennifer and I maneuvered Dad into the wheelchair. Jennifer thought that he was a bit weaker than yesterday and said that she wanted him back in bed in about an hour. It was a nice day, so after I had Dad cough up some secretions, we headed outside in the wheelchair. We strolled on all of the available sidewalks, which still wasn’t much of an outing, and then settled under the covered hospital entrance. While we were sitting out front, Stan and Mom drove up and visited. Stan could stay for only a couple of minutes because they had been grocery shopping and he had to get the perishables home. Mom and I visited outside with Dad until 3:25 P.M. Shortly after the three of us returned to Dad’s room, Jennifer, Hector, and I put him back in bed. Mom and I visited with Dad until about 4:30 P.M.

I returned to the hospital at 2:00 P.M. to find that Jennifer and the aide were giving Dad a bath. When they were finished, Jennifer and I maneuvered Dad into the wheelchair. Jennifer thought that he was a bit weaker than yesterday and said that she wanted him back in bed in about an hour. It was a nice day, so after I had Dad cough up some secretions, we headed outside in the wheelchair. We strolled on all of the available sidewalks, which still wasn’t much of an outing, and then settled under the covered hospital entrance. While we were sitting out front, Stan and Mom drove up and visited. Stan could stay for only a couple of minutes because they had been grocery shopping and he had to get the perishables home. Mom and I visited outside with Dad until 3:25 P.M. Shortly after the three of us returned to Dad’s room, Jennifer, Hector, and I put him back in bed. Mom and I visited with Dad until about 4:30 P.M.

It had been another long day and Stan, Mom, and I were pooped. I had downloaded the Domino’s app to my iPad, so we ordered a pizza the 21st century way. We had ordered three pizzas since I had been staying there, which is more than I had ordered in the last 25 years. I loved to make homemade pizza, but desperate times called for takeout.

Stan and I stayed up late to watch the total lunar eclipse (blood moon). While watching the moon, my dear friend Rhoda texted me to see how I was doing. I quickly called her to let her know about the miracle and our change in plans.

Stan and I stayed up late to watch the total lunar eclipse (blood moon). While watching the moon, my dear friend Rhoda texted me to see how I was doing. I quickly called her to let her know about the miracle and our change in plans.

She was just over the moon!

When I arrived, I met Dr. Ciceri and he explained to me that Dad had something that sounded like “the Canada fungus.” He said that they planned to replace his dialysis catheter and his PIC line. The doctor had also started Dad on an antifungal. He said that he requested a TTE (transthoracic echocardiogram) for later today. I didn’t understand the significance of most of what he said, but I clearly understood what he said next. He said that Dad’s prognosis was extremely poor, that he probably had one to two months to live, and would most likely die in a nursing home.

When I arrived, I met Dr. Ciceri and he explained to me that Dad had something that sounded like “the Canada fungus.” He said that they planned to replace his dialysis catheter and his PIC line. The doctor had also started Dad on an antifungal. He said that he requested a TTE (transthoracic echocardiogram) for later today. I didn’t understand the significance of most of what he said, but I clearly understood what he said next. He said that Dad’s prognosis was extremely poor, that he probably had one to two months to live, and would most likely die in a nursing home. At 9:40 P.M., I was awakened by the house phone, and I ran to answer it before it woke Mom. As far as we were concerned, there was nothing worse than a nighttime phone call. My parents’ phone system had an audio caller ID. My heart practically stopped when I heard it announce that the call was from Scott & White. The call was from Jeliza, Dad’s nurse. According to her, Dad insisted that he wanted to go home and that he had seen Mom in the hall. He kept calling out for her, and the nurse couldn’t calm him. She hoped that my mother or I might be more successful. Jeliza held up the phone to Dad’s ear while I explained to him that we had been in his room until 6:00 P.M., but that he had been asleep. He asked me when we would return to see him again, and when I said, “tomorrow,” he asked if we’d come by early. When I told him that we’d see him after dialysis, he said that he wasn’t going to dialysis anymore and that he would go someplace else. I explained that going someplace else would require advance planning and that we couldn’t make alternative plans on a Sunday night. I promised him that Mom and I would be there and that I’d visit with him before I left for Houston. He agreed to that plan and we said good night. The nurse took back the phone and thanked me for talking with him.

At 9:40 P.M., I was awakened by the house phone, and I ran to answer it before it woke Mom. As far as we were concerned, there was nothing worse than a nighttime phone call. My parents’ phone system had an audio caller ID. My heart practically stopped when I heard it announce that the call was from Scott & White. The call was from Jeliza, Dad’s nurse. According to her, Dad insisted that he wanted to go home and that he had seen Mom in the hall. He kept calling out for her, and the nurse couldn’t calm him. She hoped that my mother or I might be more successful. Jeliza held up the phone to Dad’s ear while I explained to him that we had been in his room until 6:00 P.M., but that he had been asleep. He asked me when we would return to see him again, and when I said, “tomorrow,” he asked if we’d come by early. When I told him that we’d see him after dialysis, he said that he wasn’t going to dialysis anymore and that he would go someplace else. I explained that going someplace else would require advance planning and that we couldn’t make alternative plans on a Sunday night. I promised him that Mom and I would be there and that I’d visit with him before I left for Houston. He agreed to that plan and we said good night. The nurse took back the phone and thanked me for talking with him.

Mom and I arrived at the

Mom and I arrived at the

Every morning, the doctor, nurses, or both, performed a short assessment of Dad’s mental status. From the third week after he entered the Scott & White system, he had been unable to tell the medical providers the name of the president of the United States. Although there might have been a few days in which he couldn’t remember, I suspect that most of the time he was being stubborn. He wasn’t a fan of President Obama and forgetting his name was a personal protest of Dad’s. I sometimes wondered if his refusal to acknowledge the president affected the assessment of his mental status.

Every morning, the doctor, nurses, or both, performed a short assessment of Dad’s mental status. From the third week after he entered the Scott & White system, he had been unable to tell the medical providers the name of the president of the United States. Although there might have been a few days in which he couldn’t remember, I suspect that most of the time he was being stubborn. He wasn’t a fan of President Obama and forgetting his name was a personal protest of Dad’s. I sometimes wondered if his refusal to acknowledge the president affected the assessment of his mental status.

September 12. Mom and I arrived at the CCH at 8:00 A.M. Dad was still restrained and his call button was on the floor. John, Dad’s nurse, told us that his heart rate had been elevated to 135 and he became

September 12. Mom and I arrived at the CCH at 8:00 A.M. Dad was still restrained and his call button was on the floor. John, Dad’s nurse, told us that his heart rate had been elevated to 135 and he became

I left the CCH at 11:40 A.M. to have lunch at the house with Mom and Stan. They had stayed at the house to do some yard work. Mom had found a couple of snake skins, which I took to use with some of my lumen printing. I thought that they might add a nice touch to my fig leaf prints.

I left the CCH at 11:40 A.M. to have lunch at the house with Mom and Stan. They had stayed at the house to do some yard work. Mom had found a couple of snake skins, which I took to use with some of my lumen printing. I thought that they might add a nice touch to my fig leaf prints. Mom and I arrived at Dad’s room around 9:15 A.M. Dad was getting an IV for a heart flutter. I asked the doctor about his restraints and about his plan for removing them. Because the

Mom and I arrived at Dad’s room around 9:15 A.M. Dad was getting an IV for a heart flutter. I asked the doctor about his restraints and about his plan for removing them. Because the  When we were ready to return to the air conditioning, I tried the back door buzzer, which notified the nurses’ station that someone was at the receiving entrance. The nurses kindly told me that it wasn’t safe to go out that door. I took Dad out for one more spin, but through the front door. When we returned to his room, he said that he wanted to go back to his room. I told him that he was in his room. To orient him to his surroundings, I backed him out of his room and pushed him back in. I also showed him his sunflowers and told him that as long as he saw those flowers, he was in his room. He then fell fast asleep. We called Michelle, his nurse, to tell her that we were leaving. She fastened a gait belt around him so that he wouldn’t slide out of the chair and said that they would move him back to bed before the shift change. Mom and I then left at 4:30. We stopped off at HEB and picked up a pizza for our dinner.

When we were ready to return to the air conditioning, I tried the back door buzzer, which notified the nurses’ station that someone was at the receiving entrance. The nurses kindly told me that it wasn’t safe to go out that door. I took Dad out for one more spin, but through the front door. When we returned to his room, he said that he wanted to go back to his room. I told him that he was in his room. To orient him to his surroundings, I backed him out of his room and pushed him back in. I also showed him his sunflowers and told him that as long as he saw those flowers, he was in his room. He then fell fast asleep. We called Michelle, his nurse, to tell her that we were leaving. She fastened a gait belt around him so that he wouldn’t slide out of the chair and said that they would move him back to bed before the shift change. Mom and I then left at 4:30. We stopped off at HEB and picked up a pizza for our dinner.

Addison, one of the

Addison, one of the  When the three of us arrived at the house, Mom told us that last night she had washed her slippers and had left them on the bench in the courtyard.When she woke up today, only one slipper remained. The neighbors share stories of the wildlife in the area. I decided to try my luck slipper hunting in the backyard. Sure enough, I found it under a tree, none the worse for wear. Something that seemed like a tasty treat must have left its predator with a little dry mouth. Dad would love this story.

When the three of us arrived at the house, Mom told us that last night she had washed her slippers and had left them on the bench in the courtyard.When she woke up today, only one slipper remained. The neighbors share stories of the wildlife in the area. I decided to try my luck slipper hunting in the backyard. Sure enough, I found it under a tree, none the worse for wear. Something that seemed like a tasty treat must have left its predator with a little dry mouth. Dad would love this story.

When Mom and I arrived at the CCH at 7:45 A.M., Dad was sleeping. A few minutes later, the respiratory therapist woke him, finished his breathing treatment, and administered his oral care. While she was finishing her session with Dad,

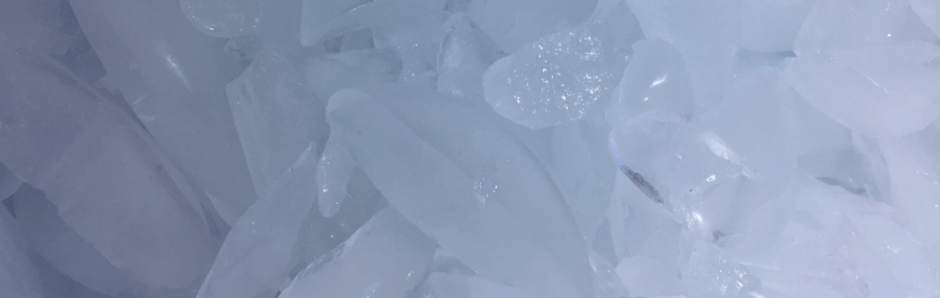

When Mom and I arrived at the CCH at 7:45 A.M., Dad was sleeping. A few minutes later, the respiratory therapist woke him, finished his breathing treatment, and administered his oral care. While she was finishing her session with Dad,  At 2:55 P.M., Holly stopped by for a bedside swallow assessment. She came armed with ice, grape juice, and pudding, but Dad totally refused to participate. I couldn’t take it for another minute. After trying unsuccessfully to get him to exert any effort, I yelled at him and left the building. By 3:05 P.M. I was in my car and on my way home. Between the numerous obstacles and his inability to overcome them, I was frustrated to the breaking point and I felt like I was about to explode. I stopped by the house to pick up my computer and drove home–fuming all the way. Once again, it seemed like Dad’s biggest obstacle was Dad.

At 2:55 P.M., Holly stopped by for a bedside swallow assessment. She came armed with ice, grape juice, and pudding, but Dad totally refused to participate. I couldn’t take it for another minute. After trying unsuccessfully to get him to exert any effort, I yelled at him and left the building. By 3:05 P.M. I was in my car and on my way home. Between the numerous obstacles and his inability to overcome them, I was frustrated to the breaking point and I felt like I was about to explode. I stopped by the house to pick up my computer and drove home–fuming all the way. Once again, it seemed like Dad’s biggest obstacle was Dad. Mom had been encouraged

Mom had been encouraged

With the exception of a couple of golf tournaments, Dad hadn’t been watching any television since May 6. To catch him up on the latest political happenings, Mom brought him the Newsweek magazine that had Donald Trump’s picture on the cover. At the time, Mr. Trump still didn’t seem like he’d make it to the general election, let alone the White House.

With the exception of a couple of golf tournaments, Dad hadn’t been watching any television since May 6. To catch him up on the latest political happenings, Mom brought him the Newsweek magazine that had Donald Trump’s picture on the cover. At the time, Mr. Trump still didn’t seem like he’d make it to the general election, let alone the White House. Today was dialysis day, so Mom and I spent the morning at home doing chores and picked 284 tomatoes from the vegetable garden. We had picked so many tomatoes this summer that Mom and I were eating tomato sandwiches every day—sometimes twice a day. We arrived at the CCH at 12:30 P.M. and encountered

Today was dialysis day, so Mom and I spent the morning at home doing chores and picked 284 tomatoes from the vegetable garden. We had picked so many tomatoes this summer that Mom and I were eating tomato sandwiches every day—sometimes twice a day. We arrived at the CCH at 12:30 P.M. and encountered  August 23. Sundays at the CCH were pretty uneventful. There was no dialysis or therapies and you didn’t see the doctors after the morning rounds unless there was a problem. You’d think that the parking lot would be full of cars, but the CCH wasn’t teeming with visitors. The place seemed empty, dark, and depressing. The doctors at Memorial had told me on more than one occasion that a primary reason for transferring Dad from the ICU to the CCH was so that he could be exposed to more light. These rooms had small windows and even with all the light on, the rooms still seemed dark.

August 23. Sundays at the CCH were pretty uneventful. There was no dialysis or therapies and you didn’t see the doctors after the morning rounds unless there was a problem. You’d think that the parking lot would be full of cars, but the CCH wasn’t teeming with visitors. The place seemed empty, dark, and depressing. The doctors at Memorial had told me on more than one occasion that a primary reason for transferring Dad from the ICU to the CCH was so that he could be exposed to more light. These rooms had small windows and even with all the light on, the rooms still seemed dark. Dr. Stewart then told me and Mom that he wanted to meet with us in a conference room to consult with us about some of Dad’s future possibilities. He started off this consultation by stating that they considered Dad’s recovery to be one of their best achievements and acknowledged our part in that success. He went on to say that he suspected that if Dad did go home, he could have more episodes of pneumonia. He continued by saying that Dad might never fully develop the ability to swallow, and if he did, he could very likely choke on his food and develop pneumonia again. He went on to say that although Dad might never be able to eat peas and carrots, we should let him eat what he wants, regardless of the consequences. He said that there was a good chance that Dad would go home with a trach tube. After that disheartening meeting with one of our favorite caregivers, Mom and I returned to Dad’s room.

Dr. Stewart then told me and Mom that he wanted to meet with us in a conference room to consult with us about some of Dad’s future possibilities. He started off this consultation by stating that they considered Dad’s recovery to be one of their best achievements and acknowledged our part in that success. He went on to say that he suspected that if Dad did go home, he could have more episodes of pneumonia. He continued by saying that Dad might never fully develop the ability to swallow, and if he did, he could very likely choke on his food and develop pneumonia again. He went on to say that although Dad might never be able to eat peas and carrots, we should let him eat what he wants, regardless of the consequences. He said that there was a good chance that Dad would go home with a trach tube. After that disheartening meeting with one of our favorite caregivers, Mom and I returned to Dad’s room.