August 3, 2015. It had now been 90 days since Dad first entered the hospital for his seven-to-ten day stay. When Mom and I arrived at 7:45 A.M., Dad’s room was a hubbub of activity. Dr. Phan, the nephrology resident, was assessing him and Emily, his nurse, was exercising his arms and legs. But the first thing that we noticed was Dad’s bed. Yesterday, Dr. Jimenez had told Dad’s nurse that he wanted to see Dad’s bed raised to a more upright position. I had envisioned that the angle of his bed would change from 30 to 75 degrees. What we saw instead was a bed that had morphed into a chair. It played music, automatically adjusted to specific angles, and could change into a chair. Was there anything that this bed couldn’t do?

August 3, 2015. It had now been 90 days since Dad first entered the hospital for his seven-to-ten day stay. When Mom and I arrived at 7:45 A.M., Dad’s room was a hubbub of activity. Dr. Phan, the nephrology resident, was assessing him and Emily, his nurse, was exercising his arms and legs. But the first thing that we noticed was Dad’s bed. Yesterday, Dr. Jimenez had told Dad’s nurse that he wanted to see Dad’s bed raised to a more upright position. I had envisioned that the angle of his bed would change from 30 to 75 degrees. What we saw instead was a bed that had morphed into a chair. It played music, automatically adjusted to specific angles, and could change into a chair. Was there anything that this bed couldn’t do?

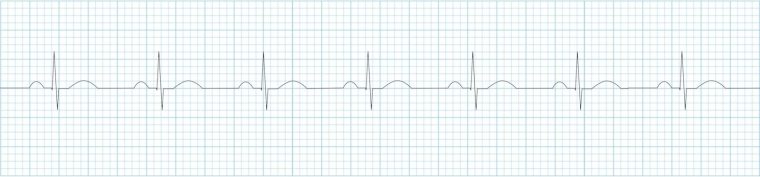

Emily greeted us with a mixed bag of information. She told us that Dad had been off all of his vasopressors since 1:30 A.M. and that Dad had squeezed the doctor’s hand this morning in response to a verbal command. On top of that good news, the respiratory therapist had switched over his ventilator to CPAP, so Dad was now breathing on his own. I would have been over the moon, except his WBC count was now 19.7, which was up from 18.0. I was obsessed with his WBC count and noticed that it had been inching up for the past two days.

Under normal circumstances, the attending physician starts on Friday; however, life at the hospital had been anything but normal. Two weeks earlier, the director of the Medical ICU died in a freak accident at his home in Salado. Aside from the loss of an extremely well-liked coworker, the doctors’ schedules were shuffled to fill the administrative duties left by his passing. This shuffling of schedules resulted in the early departure of Dr. Jimenez and the early arrival of Dr. Yau as the new attending physician.

Dr. Yau said that he would order a CT scan to see if Dad had an infection outside of his lungs that could be drained, which would help lower Dad’s WBC count. On a more positive note, he said that it seemed that Dad’s kidneys had finally decided to wake up and start making urine. The day seemed to be going better than I could have expected. I hated to leave, but I had to return to my parents’ house to attend a noon meeting for work.

Shortly after I got home, my day started taking a downward turn when the internet service stopped working. With the internet being my primary connection to my job, I didn’t accomplish much for the remainder of the day.

Things weren’t going much better in my father’s room. From what my mother observed, Dad would not stop pulling on his feeding tube, CPAP connector, and trach tube. Mom was also upset because it seemed to her that Dad didn’t recognize (or acknowledge) her. Even worse, he seemed to regard her with some contempt, although he seemed pretty happy when the nurse was in the room. Because he was unable to communicate with us, we were very confused about his behavior and what he was thinking.

While Mom and I were at home for dinner, I printed out some recent photos of Dad with the family. I wanted the hospital personnel to see him as more than the sick man that they attended in that hospital bed. He hadn’t entered the hospital as some sickly old man, and I wanted them to have a sense of who he was just a few months earlier. After dinner, Mom and I returned to the hospital around 6:50 P.M. and learned that Dustin was Dad’s nurse. I wasn’t impressed with this nurse, and I wasn’t thrilled to see him again.

While Mom and I were at home for dinner, I printed out some recent photos of Dad with the family. I wanted the hospital personnel to see him as more than the sick man that they attended in that hospital bed. He hadn’t entered the hospital as some sickly old man, and I wanted them to have a sense of who he was just a few months earlier. After dinner, Mom and I returned to the hospital around 6:50 P.M. and learned that Dustin was Dad’s nurse. I wasn’t impressed with this nurse, and I wasn’t thrilled to see him again.

Dad seemed agitated again. In an attempt to calm him, I held his hand and talked to him for about an hour. He seemed to be calming down when the respiratory therapist stopped by to administer the oral treatment, but as soon as she left, Dad vomited. With his history of aspiration, I was a little freaked out. I quickly grabbed a nurse in the hall, and she got Dustin, who was seated at the nurses’ station. I wondered if he had been agitated because he felt nauseated. I’d never know.

After contacting the on-call resident, they decided to stop Dad’s tube feed for the remainder of the night. The doctor also ordered an x-ray and the nurse pulled out all the remaining fluid in Dad’s stomach. It seemed disgusting, but with the feeding tube, the nurse could use a syringe to withdraw the Nepro in his stomach. They occasionally suctioned his stomach contents to see how fast the tube feed was being absorbed by his system, and then they’d return the Nepro into his stomach. Something that once might have seemed pretty disgusting now was part of our daily routine.

At 8:25 P.M., Dustin and another nurse repositioned Dad and adjusted the back of his bed to a 45-degree angle. Tube feed-patients were usually kept at a 30-degree angle, so Dad was now a bit more elevated than usual.

As Mom and I were leaving for the night, Dustin told us that they would x-ray Dad sometime around 3:00 A.M tomorrow morning to see if he had aspirated anything when he vomited.

In addition to 90 days being a long hospital stay, it also marked the end of his annual insured Medicare days. From this point forward, he’d be drawing against his one-time reserve of 60 days. Surely he’d be home in less than 60 days.

August 4. Mom and I arrived to Dad’s room at 7:45 A.M. Dr. Brett Ambroson, one of the residents, was assessing Dad. He provided us with a brief update about the CT scan and x-ray, assuring us that Dad had not aspirated the Nepro last night. He also confirmed that Dad was still off all of the vasopressors. Shortly after Dr. Ambroson left, Dr. Adam Hayek, one of our favorite fellows, stopped by to see if we had any questions. While he was in the room, Dr. Hayak mentioned that Dad had vomited again during the night, so until the doctor stopped by on his rounds, the tube feed would be withheld.

For the first time since his readmittance to the hospital, Dad motioned for me to give him a kiss, and he smiled at me.

At 11:00 A.M, Travis, the physical therapist, stopped by to see if he could get Dad into a cardiac chair. Travis couldn’t find a cardiac chair, so he tried to get Dad to the side of the bed. Dad was pretty weak, and Travis had one heck of a time moving Dad. Fortunately, Heather, another physical therapist, stopped in to help him. Dad didn’t actually sit on the side of the bed, but they established a baseline of Dad’s strength. Travis said that he’d try to find a cardiac chair for Dad later in the day. I didn’t know what a cardiac chair was, but if Dad could barely sit on the site of the bed, I didn’t understand how he could get into a chair.

Just before we left for lunch, Pastor Don stopped by for a short visit and a much-needed prayer. Although Dad had seemed happy to see us, I wasn’t feeling as positive this morning about his status as I had been just 24 hours earlier. Although Dad’s condition was no longer grave, it was guarded, which diminished my anxiety only slightly.

As mom walked back into Dad’s room after lunch, Dad was pulling out his feeding tube again. Mom alerted Chris, the charge nurse, who secured the tube with a little tape and some glue.

Dr. Howell stopped by and said that the antibiotic that Dad was taking was very strong and that they wanted to hold it in reserve and not use it unless absolutely necessary. He added that it could take as much as four weeks to clear up the infection. Four weeks. That was over half of our remaining Medicare coverage time. I wondered if Dad would have to remain in the hospital until the infection was gone. His WBC count had inched up again overnight, and I was becoming more anxious about this infection.

At 3:30 P.M., the nurse gave Dad some Zofran for nausea, and told us that the tube feed would resume later that evening.

I had been at home working since lunchtime and returned to the hospital at 6:30 P.M. Sarah, the night nurse, came in at 7:05 A.M. to perform her evening assessment. Dad didn’t respond well to her commands, but I had a sense that he could if he wanted to. He was very frustrated and it seemed to me that he was losing his will. I talked to him for a long time, but I didn’t think that I made much progress with him.

Since Dad had become aware of his surroundings, we had talked to him about what was going on around him and the state of his health, but we had not told him what had happened to him at the CCH. For him, it probably seemed like one minute he was in dialysis and the next minute he was waking up in the hospital, hooked up to machines and unable to communicate. Stan, Mom, and I agreed that we should tell him what happened. Maybe tomorrow.

I had never heard about procalcitonin (PCT) until today, when Dr. Jimenez mentioned that Dad’s current level was 48—down from 64. As soon as the doctor left the room, I whipped out my iPad and searched the internet for information about PCT. From what I read, a PCT level greater than 10 indicated a “high likelihood of severe sepsis or septic shock.” You didn’t have to be a PhD to know that a PCT level of 48 was pretty bad.

I had never heard about procalcitonin (PCT) until today, when Dr. Jimenez mentioned that Dad’s current level was 48—down from 64. As soon as the doctor left the room, I whipped out my iPad and searched the internet for information about PCT. From what I read, a PCT level greater than 10 indicated a “high likelihood of severe sepsis or septic shock.” You didn’t have to be a PhD to know that a PCT level of 48 was pretty bad. When Dr. Jimenez and his entourage entered the room, he said that Dad was “one tough guy.” He said something about an albumin transfusion (protein) to help with absorption, but I was too excited to remember everything that he said. Mom and I knew that Dad was still in the woods, but we felt that he had finally found the path out. Before the doctor left, he told Melissa, the nurse, that he wanted the bed raised to more of a sitting position. This day also marked the first day since my father’s return that we didn’t hear something about his grave prognosis.

When Dr. Jimenez and his entourage entered the room, he said that Dad was “one tough guy.” He said something about an albumin transfusion (protein) to help with absorption, but I was too excited to remember everything that he said. Mom and I knew that Dad was still in the woods, but we felt that he had finally found the path out. Before the doctor left, he told Melissa, the nurse, that he wanted the bed raised to more of a sitting position. This day also marked the first day since my father’s return that we didn’t hear something about his grave prognosis. Shortly after 10:00 A.M., we met

Shortly after 10:00 A.M., we met  When Dad was transferred from the CCH to Memorial, his flowers could not come with him. Cut flowers and plants are not permitted in the ICU. I had been thinking about it for a couple of days, and I was now determined to brighten up Dad’s room. After lunch, I cleaned the vase that had held his sunflower arrangement, took it back to

When Dad was transferred from the CCH to Memorial, his flowers could not come with him. Cut flowers and plants are not permitted in the ICU. I had been thinking about it for a couple of days, and I was now determined to brighten up Dad’s room. After lunch, I cleaned the vase that had held his sunflower arrangement, took it back to  July 28, 2015. Six days since Dad returned to

July 28, 2015. Six days since Dad returned to  The big surprise of the week occurred right after Dr. White left Dad’s room. During the procession of residents and the attending physician, a woman kept appearing in the doorway, and would then leave. When the room was finally empty of providers, she entered Dad’s room and introduced herself as Aimee from the Patient Relations department. She told us that a hospital employee had contacted her office about Dad, and suggested that she meet with us about the events that led to his return to Memorial. I pulled out my iPad of notes and shared our concerns about some of our interactions with one of the CCH doctors. Aimee told us that they would investigate our complaint and get back to us in 30 days. I assured her that although we had complaints about one person, for the most part, we were pleased with the level of care that Dad had received from his providers. When she left, Mom and I were stunned and kept trying to guess who contacted Aimee’s office.

The big surprise of the week occurred right after Dr. White left Dad’s room. During the procession of residents and the attending physician, a woman kept appearing in the doorway, and would then leave. When the room was finally empty of providers, she entered Dad’s room and introduced herself as Aimee from the Patient Relations department. She told us that a hospital employee had contacted her office about Dad, and suggested that she meet with us about the events that led to his return to Memorial. I pulled out my iPad of notes and shared our concerns about some of our interactions with one of the CCH doctors. Aimee told us that they would investigate our complaint and get back to us in 30 days. I assured her that although we had complaints about one person, for the most part, we were pleased with the level of care that Dad had received from his providers. When she left, Mom and I were stunned and kept trying to guess who contacted Aimee’s office. His pulse was running in the 130s again, and his oxygen saturation levels were low. To compensate for the low oxygen levels, the respiratory therapist increased his oxygen levels on the ventilator to 60%. A few minutes later, the ventilator started alarming, which prompted the nurse to page the respiratory therapist. Evidently, one piece of the ventilator was cross-threaded, which was what caused the system to alarm. The alarms were starting to drive us crazy and I could swear that I could hear them when we were away from the hospital.

His pulse was running in the 130s again, and his oxygen saturation levels were low. To compensate for the low oxygen levels, the respiratory therapist increased his oxygen levels on the ventilator to 60%. A few minutes later, the ventilator started alarming, which prompted the nurse to page the respiratory therapist. Evidently, one piece of the ventilator was cross-threaded, which was what caused the system to alarm. The alarms were starting to drive us crazy and I could swear that I could hear them when we were away from the hospital. When Dr. White and his band of providers arrived outside of Dad’s room, I heard comments about Dad being

When Dr. White and his band of providers arrived outside of Dad’s room, I heard comments about Dad being  Shortly before 4:00 P.M., I was presented with a

Shortly before 4:00 P.M., I was presented with a  Carlos, the dialysis nurse, arrived at 8:15 A.M. and proceeded to prepare Dad for dialysis. At the same time, Dr. Fernandez, one of the

Carlos, the dialysis nurse, arrived at 8:15 A.M. and proceeded to prepare Dad for dialysis. At the same time, Dr. Fernandez, one of the  At 2:15 P.M., the hematology team arrived. Because Dad’s lab work showed that he had

At 2:15 P.M., the hematology team arrived. Because Dad’s lab work showed that he had  Dad’s oxygen levels had been fair, and when Nikita, the respiratory therapist arrived, she increased his oxygen level on the ventilator from 40% to 50%. As she adjusted the ventilator settings, she said that she’d probably decrease the levels back to 40% later in the day.

Dad’s oxygen levels had been fair, and when Nikita, the respiratory therapist arrived, she increased his oxygen level on the ventilator from 40% to 50%. As she adjusted the ventilator settings, she said that she’d probably decrease the levels back to 40% later in the day. When we returned to Dad’s room at 7:00 P.M., we were thrilled to see that Tyler was Dad’s night nurse again. Nights were scary for me and Mom, and knowing that Dad was in good hands gave us some peace of mind. Dad’s vasopressor dosage had inched down again, which was also wonderful to see. Unfortunately, the oxygen setting on the ventilator was still set to 50%, which meant that Dad’s

When we returned to Dad’s room at 7:00 P.M., we were thrilled to see that Tyler was Dad’s night nurse again. Nights were scary for me and Mom, and knowing that Dad was in good hands gave us some peace of mind. Dad’s vasopressor dosage had inched down again, which was also wonderful to see. Unfortunately, the oxygen setting on the ventilator was still set to 50%, which meant that Dad’s  July 26, 2015. Mom and I arrived at the hospital shortly after 8:00 A.M.; I looked at Dad, and then over to his IVs. Amazingly, Dad’s night nurse, Tyler, had been able to wean Dad down to one

July 26, 2015. Mom and I arrived at the hospital shortly after 8:00 A.M.; I looked at Dad, and then over to his IVs. Amazingly, Dad’s night nurse, Tyler, had been able to wean Dad down to one  When Dr. White arrived, he acknowledged that while there had been some clinical improvement in my dad’s condition, Dad was still critically ill and his mental status was not improving. To ensure that Dad hadn’t suffered a stroke or a bleed, he planned to order a CT scan. Dr. White restated his concern about Dad’s toes and thought that he probably would lose at least one toe.

When Dr. White arrived, he acknowledged that while there had been some clinical improvement in my dad’s condition, Dad was still critically ill and his mental status was not improving. To ensure that Dad hadn’t suffered a stroke or a bleed, he planned to order a CT scan. Dr. White restated his concern about Dad’s toes and thought that he probably would lose at least one toe. While Mom, Stan, and I were at home for lunch, I decided I would try some music therapy with Dad.

While Mom, Stan, and I were at home for lunch, I decided I would try some music therapy with Dad.  July 24, 2015. The call that we dreaded from the hospital during the night hadn’t come.

July 24, 2015. The call that we dreaded from the hospital during the night hadn’t come.

Mom and I went home for dinner and returned to the hospital at 7:15 P.M. Charlie, the respiratory therapist, had just finished Dad’s trach and oral care and ventilator maintenance. Dad was still on three vasopressors. Mom and I met Donna, the night nurse, before leaving for the night. She told us that Dad had additional blood draw after dialysis and that his WBC count was now 22.7, up another 4 points from this morning. His WBC count hadn’t increased at this rate since

Mom and I went home for dinner and returned to the hospital at 7:15 P.M. Charlie, the respiratory therapist, had just finished Dad’s trach and oral care and ventilator maintenance. Dad was still on three vasopressors. Mom and I met Donna, the night nurse, before leaving for the night. She told us that Dad had additional blood draw after dialysis and that his WBC count was now 22.7, up another 4 points from this morning. His WBC count hadn’t increased at this rate since  Now that Dad was back on the ventilator, he couldn’t talk. I got some wild idea yesterday that I had to give Dad a chance to communicate with us if he was going to die. Andrea said that she would contact the respiratory therapist to see if it would be possible to enable him to talk. The respiratory therapist contacted Svenja, the Trach Goddess of Scott & White. We hadn’t seen her since June, when she first

Now that Dad was back on the ventilator, he couldn’t talk. I got some wild idea yesterday that I had to give Dad a chance to communicate with us if he was going to die. Andrea said that she would contact the respiratory therapist to see if it would be possible to enable him to talk. The respiratory therapist contacted Svenja, the Trach Goddess of Scott & White. We hadn’t seen her since June, when she first  When I got off the telephone with Dr. Anderson, I texted Pastor Don and my husband about Dad’s situation. Mom and I got dressed and headed to Memorial. We didn’t know where to go, so we headed to what we knew: the Cardiothoracic Intensive Care Unit (

When I got off the telephone with Dr. Anderson, I texted Pastor Don and my husband about Dad’s situation. Mom and I got dressed and headed to Memorial. We didn’t know where to go, so we headed to what we knew: the Cardiothoracic Intensive Care Unit ( Evidently, when Dad arrived from the CCH, he was on three

Evidently, when Dad arrived from the CCH, he was on three  Throughout Dad’s stay in the Scott & White system, I had developed a steely resolve to stay positive and to keep my parents positive. The last six hours had severely cracked my armor. When Charis first entered the room to talk with us about Dad and how the doctors were expecting his death, I sort of lost it. While fighting back tears, I started telling her that what I was feeling was like

Throughout Dad’s stay in the Scott & White system, I had developed a steely resolve to stay positive and to keep my parents positive. The last six hours had severely cracked my armor. When Charis first entered the room to talk with us about Dad and how the doctors were expecting his death, I sort of lost it. While fighting back tears, I started telling her that what I was feeling was like  When Mom and I went to lunch, we stopped by the CCH to pick up Dad’s belongings and flowers. Live flowers are not allowed in the ICU at Memorial. When we returned to Memorial around 2:30 P.M., he was wrapped in a Bair Hugger (heating blanket). His core temperature was now too low, partly because of the dialysis, and they needed to raise it.

When Mom and I went to lunch, we stopped by the CCH to pick up Dad’s belongings and flowers. Live flowers are not allowed in the ICU at Memorial. When we returned to Memorial around 2:30 P.M., he was wrapped in a Bair Hugger (heating blanket). His core temperature was now too low, partly because of the dialysis, and they needed to raise it. Wednesday, July 22, 2015: 3:45 P.M. I had just left a meeting at work and listened to the voicemail that my mother left 40 minutes earlier. “Melody, it’s Mom. I’m at the hospital with Dad and he’s not doing too well. He had a bad coughing spell during dialysis and they’re trying to bring his blood pressure down, but he’s got the shakes and delusions and all kinds of stuff. Call me on my cell, because I’m not going to leave him. Talk to you later. Bye-bye.”

Wednesday, July 22, 2015: 3:45 P.M. I had just left a meeting at work and listened to the voicemail that my mother left 40 minutes earlier. “Melody, it’s Mom. I’m at the hospital with Dad and he’s not doing too well. He had a bad coughing spell during dialysis and they’re trying to bring his blood pressure down, but he’s got the shakes and delusions and all kinds of stuff. Call me on my cell, because I’m not going to leave him. Talk to you later. Bye-bye.”