July 27, 2015. I was working from my parents’ home, and I would log on to my office network at 3:45 A.M. I had coworkers in India and Israel, and by starting at this time, I could work with them for two or three hours before I went to the hospital.

Shortly after 4:30 A.M., it occurred to me that my Millennial cousin might be more of a texter than an emailer. To ensure that he would read my email that I sent him last night, I texted him to tell him that I had emailed him the previous night. Sure enough, about an hour later he called me on my mobile phone. He wasn’t able to give me many answers, but he did provide me with information that I could research further so that I could converse with the doctors and ask reasonably intelligent questions.

Mom and I arrived at the hospital at 8:00 A.M., only to learn that Dad was still unresponsive. According to Kristina, his nurse, he would open his eyes and grimace only to a sternal rub and other painful stimuli. The sternal rub can be painful for anyone, but Dad had just had open-heart surgery a couple of months earlier, and I couldn’t bear to watch this exercise. He would not respond to or follow any verbal commands. I later watched the doctor inflict this pain, and it was hard to watch. Worse yet was the slow-motion response from my father. It’s an image that I can’t shake.

Carlos, the dialysis nurse, arrived at 8:15 A.M. and proceeded to prepare Dad for dialysis. At the same time, Dr. Fernandez, one of the fellows who worked in the ICU, performed a brief assessment of Dad’s condition. Following his assessment, he sat down with me and Mom and told us how pleased he was to see our devotion and attention to Dad, and added that he wished that all his patients had families like us. As he left us, he said that he thought that our prayers would be answered. It was a moment that would carry us for a few days.

Carlos, the dialysis nurse, arrived at 8:15 A.M. and proceeded to prepare Dad for dialysis. At the same time, Dr. Fernandez, one of the fellows who worked in the ICU, performed a brief assessment of Dad’s condition. Following his assessment, he sat down with me and Mom and told us how pleased he was to see our devotion and attention to Dad, and added that he wished that all his patients had families like us. As he left us, he said that he thought that our prayers would be answered. It was a moment that would carry us for a few days.

Shortly after his dialysis session started, I put the radio headphones on Dad’s head. I left the headphones on him for about 30 minutes, but we still didn’t see any response.

Because Dad’s blood pressure and temperature dropped during dialysis, Dad’s nurse had to increase his vasopressor. It was discouraging to see the dosage increased, but it was still lower than it had been yesterday.

From the moment that we would arrive at the hospital, I would scan the halls to try to determine where the doctor was on his rounds and when he would arrive to Dad’s room. After he and his party arrived, I’d stand in the threshold so that I could eavesdrop on their conversation, which was usually more enlightening than his meeting with us. It’s also where I picked up some medical jargon. Today Dr. White and his entourage appeared outside Dad’s door at 10:20 A.M. As usual, he held court with his team of residents, fellows, pharmacists, and the nurse for several minutes before entering the room. He eventually agreed that things seemed to be progressing in the right direction—except Dad’s noggin. He also said that because Dad’s platelets were low again, he would request a hematology consultation. On a very positive note, the lowering of the vasopressors had improved the blood flow in Dad’s extremities, and Dad would not lose any toes!

When Mom and I returned from lunch at 1:00 P.M., we found Dr. Hildago, a neurology resident, in Dad’s room. Between the two of us, Kristina and I updated the doctor on Dad’s 83-day medical history.

After the neurology resident left, we were pleasantly surprised to see Pastor Don and his wife, Wynn, enter the room. Seeing the two of them had sort of a cleansing effect on our stressed-out emotions. Mom and I always enjoyed their visits and hated to see either one of them leave.

Dad’s tube feed had resumed yesterday, and the dietitian stopped by to assess his nutritional requirements and status. The current flow of Nepro was less than half of what it had been when he aspirated. The dietitian recommended that it be increased to 40 ml/hr, which would provide him with about 1,700 calories day.

At 2:15 P.M., the hematology team arrived. Because Dad’s lab work showed that he had Thrombocytopenia, Dr. White had requested a hematology consultation. According to the doctor, Dad’s platelets dropped when he became septic and required vasopressor support. From what the doctor said, Dad’s sepsis condition also increased his platelet consumption. To make matters worse, Dad’s infection and the antibiotics both suppressed the bone marrow production of platelets. For these reasons, the hematologists were not surprised that Dad’s platelet count continued to be low. They said that they would give him platelet transfusions whenever his platelet count dropped below 20. Following the platelet transfusion the other day, his platelet count now sat at 26, which was still pretty low.

At 2:15 P.M., the hematology team arrived. Because Dad’s lab work showed that he had Thrombocytopenia, Dr. White had requested a hematology consultation. According to the doctor, Dad’s platelets dropped when he became septic and required vasopressor support. From what the doctor said, Dad’s sepsis condition also increased his platelet consumption. To make matters worse, Dad’s infection and the antibiotics both suppressed the bone marrow production of platelets. For these reasons, the hematologists were not surprised that Dad’s platelet count continued to be low. They said that they would give him platelet transfusions whenever his platelet count dropped below 20. Following the platelet transfusion the other day, his platelet count now sat at 26, which was still pretty low.

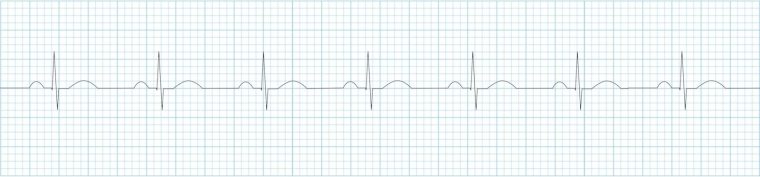

Moments after the hematology team left, Dr. Burkholder, the neurologist, arrived with a couple of residents in tow. He told us that Dad should have an EEG sometime later today and an MRI either tomorrow or the next day, depending on various schedules. This brief encounter with the doctor was typical of how we interacted with the specialists. The resident or fellow would arrive and spend quite a bit of time assessing Dad, and then the doctor would pop in for two minutes, basically repeating what the resident had told us earlier.

Dad’s oxygen levels had been fair, and when Nikita, the respiratory therapist arrived, she increased his oxygen level on the ventilator from 40% to 50%. As she adjusted the ventilator settings, she said that she’d probably decrease the levels back to 40% later in the day.

Dad’s oxygen levels had been fair, and when Nikita, the respiratory therapist arrived, she increased his oxygen level on the ventilator from 40% to 50%. As she adjusted the ventilator settings, she said that she’d probably decrease the levels back to 40% later in the day.

Kristina had shown me how to exercise Dad’s arms. When she saw me moving his arms, she showed me how I could also move his legs. I had barely started exercising his legs when the EEG tech arrived.

After the EEG, which takes longer to set up than to administer, Mom and I left the hospital to run some errands and eat dinner.

When we returned to Dad’s room at 7:00 P.M., we were thrilled to see that Tyler was Dad’s night nurse again. Nights were scary for me and Mom, and knowing that Dad was in good hands gave us some peace of mind. Dad’s vasopressor dosage had inched down again, which was also wonderful to see. Unfortunately, the oxygen setting on the ventilator was still set to 50%, which meant that Dad’s oxygenation was still shaky.

When we returned to Dad’s room at 7:00 P.M., we were thrilled to see that Tyler was Dad’s night nurse again. Nights were scary for me and Mom, and knowing that Dad was in good hands gave us some peace of mind. Dad’s vasopressor dosage had inched down again, which was also wonderful to see. Unfortunately, the oxygen setting on the ventilator was still set to 50%, which meant that Dad’s oxygenation was still shaky.

While Tyler was getting set up for the night, I exercised Dad’s arms and noticed that he seemed a little flushed. Usually the hospital room felt cold enough to set Jell-O, but for a change, Mom and I weren’t shivering. When I checked the thermostat, I noticed that it was set for 75 degrees—a setting that we hadn’t seen before and would never see again. Tyler quickly adjusted it back to 68 degrees.

When Mom and I left for the night, Tyler was oiling Dad’s dry feet and said that he planned to wash Dad’s hair. If only Tyler could work every night.

July 26, 2015. Mom and I arrived at the hospital shortly after 8:00 A.M.; I looked at Dad, and then over to his IVs. Amazingly, Dad’s night nurse, Tyler, had been able to wean Dad down to one

July 26, 2015. Mom and I arrived at the hospital shortly after 8:00 A.M.; I looked at Dad, and then over to his IVs. Amazingly, Dad’s night nurse, Tyler, had been able to wean Dad down to one  When Dr. White arrived, he acknowledged that while there had been some clinical improvement in my dad’s condition, Dad was still critically ill and his mental status was not improving. To ensure that Dad hadn’t suffered a stroke or a bleed, he planned to order a CT scan. Dr. White restated his concern about Dad’s toes and thought that he probably would lose at least one toe.

When Dr. White arrived, he acknowledged that while there had been some clinical improvement in my dad’s condition, Dad was still critically ill and his mental status was not improving. To ensure that Dad hadn’t suffered a stroke or a bleed, he planned to order a CT scan. Dr. White restated his concern about Dad’s toes and thought that he probably would lose at least one toe. While Mom, Stan, and I were at home for lunch, I decided I would try some music therapy with Dad.

While Mom, Stan, and I were at home for lunch, I decided I would try some music therapy with Dad.  July 24, 2015. The call that we dreaded from the hospital during the night hadn’t come.

July 24, 2015. The call that we dreaded from the hospital during the night hadn’t come.

Mom and I went home for dinner and returned to the hospital at 7:15 P.M. Charlie, the respiratory therapist, had just finished Dad’s trach and oral care and ventilator maintenance. Dad was still on three vasopressors. Mom and I met Donna, the night nurse, before leaving for the night. She told us that Dad had additional blood draw after dialysis and that his WBC count was now 22.7, up another 4 points from this morning. His WBC count hadn’t increased at this rate since

Mom and I went home for dinner and returned to the hospital at 7:15 P.M. Charlie, the respiratory therapist, had just finished Dad’s trach and oral care and ventilator maintenance. Dad was still on three vasopressors. Mom and I met Donna, the night nurse, before leaving for the night. She told us that Dad had additional blood draw after dialysis and that his WBC count was now 22.7, up another 4 points from this morning. His WBC count hadn’t increased at this rate since  Now that Dad was back on the ventilator, he couldn’t talk. I got some wild idea yesterday that I had to give Dad a chance to communicate with us if he was going to die. Andrea said that she would contact the respiratory therapist to see if it would be possible to enable him to talk. The respiratory therapist contacted Svenja, the Trach Goddess of Scott & White. We hadn’t seen her since June, when she first

Now that Dad was back on the ventilator, he couldn’t talk. I got some wild idea yesterday that I had to give Dad a chance to communicate with us if he was going to die. Andrea said that she would contact the respiratory therapist to see if it would be possible to enable him to talk. The respiratory therapist contacted Svenja, the Trach Goddess of Scott & White. We hadn’t seen her since June, when she first  When I got off the telephone with Dr. Anderson, I texted Pastor Don and my husband about Dad’s situation. Mom and I got dressed and headed to Memorial. We didn’t know where to go, so we headed to what we knew: the Cardiothoracic Intensive Care Unit (

When I got off the telephone with Dr. Anderson, I texted Pastor Don and my husband about Dad’s situation. Mom and I got dressed and headed to Memorial. We didn’t know where to go, so we headed to what we knew: the Cardiothoracic Intensive Care Unit ( Evidently, when Dad arrived from the CCH, he was on three

Evidently, when Dad arrived from the CCH, he was on three  Throughout Dad’s stay in the Scott & White system, I had developed a steely resolve to stay positive and to keep my parents positive. The last six hours had severely cracked my armor. When Charis first entered the room to talk with us about Dad and how the doctors were expecting his death, I sort of lost it. While fighting back tears, I started telling her that what I was feeling was like

Throughout Dad’s stay in the Scott & White system, I had developed a steely resolve to stay positive and to keep my parents positive. The last six hours had severely cracked my armor. When Charis first entered the room to talk with us about Dad and how the doctors were expecting his death, I sort of lost it. While fighting back tears, I started telling her that what I was feeling was like  When Mom and I went to lunch, we stopped by the CCH to pick up Dad’s belongings and flowers. Live flowers are not allowed in the ICU at Memorial. When we returned to Memorial around 2:30 P.M., he was wrapped in a Bair Hugger (heating blanket). His core temperature was now too low, partly because of the dialysis, and they needed to raise it.

When Mom and I went to lunch, we stopped by the CCH to pick up Dad’s belongings and flowers. Live flowers are not allowed in the ICU at Memorial. When we returned to Memorial around 2:30 P.M., he was wrapped in a Bair Hugger (heating blanket). His core temperature was now too low, partly because of the dialysis, and they needed to raise it. Wednesday, July 22, 2015: 3:45 P.M. I had just left a meeting at work and listened to the voicemail that my mother left 40 minutes earlier. “Melody, it’s Mom. I’m at the hospital with Dad and he’s not doing too well. He had a bad coughing spell during dialysis and they’re trying to bring his blood pressure down, but he’s got the shakes and delusions and all kinds of stuff. Call me on my cell, because I’m not going to leave him. Talk to you later. Bye-bye.”

Wednesday, July 22, 2015: 3:45 P.M. I had just left a meeting at work and listened to the voicemail that my mother left 40 minutes earlier. “Melody, it’s Mom. I’m at the hospital with Dad and he’s not doing too well. He had a bad coughing spell during dialysis and they’re trying to bring his blood pressure down, but he’s got the shakes and delusions and all kinds of stuff. Call me on my cell, because I’m not going to leave him. Talk to you later. Bye-bye.”