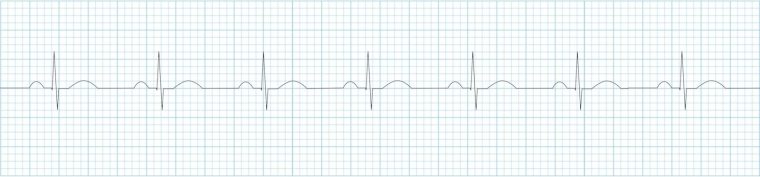

August 21, 2015. Dad’s day got off to an exciting start at 1:30 A.M. when the central monitor alarm sounded, indicating that Dad’s heart had stopped. Dad’s nurse and the charge nurse rushed into Dad’s room and found him to be very agitated. He had disconnected all of his leads and had removed his central line dressing. When the nurses explained to him that they needed to replace the leads, he struck one of them and refused to have his leads and dressing replaced. They tried to convince Dad about the importance of monitoring his heart rate and keeping his central line covered to prevent infection. Dad would not cooperate with the nurses and demanded to speak with the doctor. The nurses contacted the on-call physician and the staff nurse, both of whom came to Dad’s room. Dr. Henry, the on-call doctor, sat with Dad and talked with him for about 30 minutes. During that time, Dr. Henry told Dad that if he continued to pull out wires and lines, they’d have no choice but to restrain him. To that threat, Dad said, “Well, I’ve been restrained before.” They sedated him, put him back on CPAP support, and he eventually went back to sleep.

Today was dialysis day, so Mom and I spent the morning at home doing chores and picked 284 tomatoes from the vegetable garden. We had picked so many tomatoes this summer that Mom and I were eating tomato sandwiches every day—sometimes twice a day. We arrived at the CCH at 12:30 P.M. and encountered Dr. Smith in the lobby. He told us about how Dad had acted out overnight. He said that Dad’s MRI was not normal, but added that the MRI for an 86-year old was not normal anyway. Because the MRI wasn’t conclusive, the doctor didn’t know whether Dad’s acting out was transient or permanent. Although they could sedate him at night while he was on pressure support, they really couldn’t sedate him when he was off the ventilator. What was disturbing about last night’s event was that Dad was lucid and that he knew that he was in the hospital. Dr. Smith said that Rachel, the nurse practitioner, was working for the next couple of nights, so he’d have her check in on Dad.

Today was dialysis day, so Mom and I spent the morning at home doing chores and picked 284 tomatoes from the vegetable garden. We had picked so many tomatoes this summer that Mom and I were eating tomato sandwiches every day—sometimes twice a day. We arrived at the CCH at 12:30 P.M. and encountered Dr. Smith in the lobby. He told us about how Dad had acted out overnight. He said that Dad’s MRI was not normal, but added that the MRI for an 86-year old was not normal anyway. Because the MRI wasn’t conclusive, the doctor didn’t know whether Dad’s acting out was transient or permanent. Although they could sedate him at night while he was on pressure support, they really couldn’t sedate him when he was off the ventilator. What was disturbing about last night’s event was that Dad was lucid and that he knew that he was in the hospital. Dr. Smith said that Rachel, the nurse practitioner, was working for the next couple of nights, so he’d have her check in on Dad.

Regarding my request to have the tube feeds suspended during dialysis, Dr. Smith said that Dad’s feed rate had been reduced to 10 ml per hour during dialysis, which was a compromise between what I and Dad’s dietitian wanted. The minimal tube feeds probably weren’t in Dad’s best interest, but Dr. Smith understood my fierce concern about reducing the risk of aspiration.

During dialysis, Dad didn’t seem to exhibit any of the distress or agitation that he exhibited five hours earlier. Susan, the dialysis nurse, remarked that Dad had been very talkative during dialysis and told her about his cardiac history.

When I spoke with Dad’s nurse, Cassie, she told me that Dad had remembered her and said something like, “Long time, no see.” She said that some of his conversations would be lucid and then he would drift off to some other topic. She said that he mentioned something about seeing “Dorothy” and someone else, but Mom and I couldn’t think of who that might be. After hearing that he had also spoken about being at Jim’s house, Mom and I assumed that he was speaking about his brother, Jim, and Jim’s wife, Dora. Both Jim and Dora had been deceased for a few years.

Cassie also said that she’d check to see if Dad could be scheduled for Seroquel at night. Before I left for Houston, Cassie told me that his WBC count was 9.0, which was normal. As least something was normal.

I headed home for Houston with a heavy heart. I had been so optimistic last evening and now I was pretty concerned. Not only did he seem to be a totally different person, it now seemed as if Dad was his biggest threat to his own recovery.

Susan, the physical therapist, stopped by during the late afternoon to assess Dad’s condition and set up his goals. Dad’s strength had continued to weaken and his balance was impaired. His first goal was to be able to transfer from the bed to a chair.

Shortly after Susan left the room, Chris, the occupational therapist arrived to perform his assessment and establish goals. Unfortunately, Dad needed to progress with his physical therapy before he’d strong enough to work with the occupational therapist.

By the time Mom arrived home from the CCH and called me, I was at home in Houston. During the day, when Dad was asked where he was, he replied that he was at Walt’s house or maybe Jim’s house. Mom had to tell him that both of his brothers had been dead for several years. During their conversation, he brought up the subject of using the bathroom. During their bizarre conversation, it became apparent to Mom that Dad thought that you used the bathroom by getting on a table. When Mom explained that a table wasn’t involved, Dad wanted to know how it worked. Mom explained about toilets, and she had to spell the word. He proceeded to refer to toilets with a French accent. When they finally got off of that subject, Dad expressed an interest in getting into a wheelchair and going outside.

Fortunately, Dad had an uneventful night and didn’t require any restraints.

August 22. At 9:05 A.M., Cassie, Dad’s nurse, entered Dad’s room to find that he had decannulated himself. Just the thought of it made me queasy. Cassie called for the respiratory therapist, who reinserted his trach tube. This made two days in a row that Mom was greeted with a distressing update from Dr. Smith as she entered the CCH.

When Mom entered Dad’s room, Dad was sleeping, and he slept until 3:00 P.M. When he woke up, the respiratory therapist replaced Dad’s speaking valve. As was so often the case, the conversation turned to the subject of the bathroom. Dad insisted that all he needed was two strong men and he could get out of bed and use the bathroom.

After Mom left for the day, Dad stayed on the trach collar until 7:30 P.M. It seemed that Dad had another uneventful night. I didn’t know if he was tired from dialysis and physical therapy or if he was under the influence of his antipsychotic medications, but he slept through the night. At this point, I didn’t care why he slept. I just wanted him to get through the night without hurting himself.

August 23. Sundays at the CCH were pretty uneventful. There was no dialysis or therapies and you didn’t see the doctors after the morning rounds unless there was a problem. You’d think that the parking lot would be full of cars, but the CCH wasn’t teeming with visitors. The place seemed empty, dark, and depressing. The doctors at Memorial had told me on more than one occasion that a primary reason for transferring Dad from the ICU to the CCH was so that he could be exposed to more light. These rooms had small windows and even with all the light on, the rooms still seemed dark.

August 23. Sundays at the CCH were pretty uneventful. There was no dialysis or therapies and you didn’t see the doctors after the morning rounds unless there was a problem. You’d think that the parking lot would be full of cars, but the CCH wasn’t teeming with visitors. The place seemed empty, dark, and depressing. The doctors at Memorial had told me on more than one occasion that a primary reason for transferring Dad from the ICU to the CCH was so that he could be exposed to more light. These rooms had small windows and even with all the light on, the rooms still seemed dark.

After Mom attended church, she stopped by the CCH to see Dad. He seemed to be in pretty good spirits and wanted to talk to me. Shortly after I had eaten lunch, I received a call from Mom. She handed her cell phone to Dad. He and I tried to talk, but he couldn’t hear me very well. It seemed that he wasn’t wearing his hearing aids, so he handed the phone back to Mom. I was happy to hear that he had had an uneventful night and that the day was going well for him.

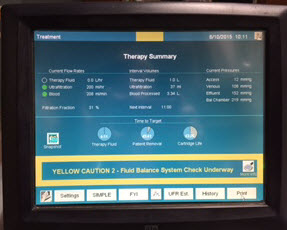

August 24. Dad’s day started with dialysis. He was starting to become confused about where he was during dialysis and it often seemed to him as if he was leaving the building or going through a series of tunnels. The trip to dialysis was actually a trip down a short hall and an elevator ride to the second floor. On this day, they removed 2,300 ml of excess fluid during dialysis, which reduced his weight from 152.9 to 144.5 pounds. On May 6, he entered Memorial weighing 161 pounds, which was a reasonable weight for a 6’1” adult male. He seemed like a shadow of his former self.

As we had been told before Dad’s transfer from Memorial a few days earlier, Dr. Heath White was back at the CCH as the presiding physician. He had now been the presiding physician for my mother during her hospitalization and for my father at each admittance at Memorial and CCH. He probably felt like we were stalking him. Dr. White found Dad to be pleasant, but confused. Dad’s WBC count was now 6.6, which was very normal and considerably lower than it was the last time that Dr. White had seen Dad and predicted his death.

Dialysis leaves most dialysis patients tired, and Dad was no exception. When Jennifer, the physical therapist assistant, stopped by at 3:30 P.M., Dad was too tired to participate. Mom asked if they could make sure to stop by on days when he didn’t have dialysis.

Cayaana, Dad’s night nurse, found Dad’s mentation to be somewhat impaired. During the start of her assessment, he seemed to be aware of his whereabouts and his situation, but after about 30 minutes, she found that she had to remind him about where he was.

Dad’s mentation problem could be challenging and was raising concerns for Mom. In particular, in honor of my mother, my father had been funding a scholarship for outstanding political science majors at Colorado Mesa University. Shell, my father’s employer for 30+ years, matched my father’s contribution. The deadline for submitting the application for 2016 was approaching. Before she left the CCH for the day, my mother mentioned the deadline to Dad. Mom was pleased to see that this topic sparked a few moments of clarity and he said that he would sign the application tomorrow.

Fortunately, his night was uneventful and he did not require restraints.

August 9, 2015. We arrived at the hospital at 9:00 A.M. to find that Dad was still asleep and restrained, the nurse’s name was not on the board, and Dad’s feeding tube was empty. Two out of three of these situations were unacceptable. I went to the nurse’s station to find out who his nurse was and to let them know that his tube feed bottle was empty. A nurse entered the room with a fresh bottle of Nepro, changed out his tubing, and replaced the empty bottle. The nurse also told me that Dad’s nurse was Nicole, who finally showed up at 9:15 A.M. and introduced herself.

August 9, 2015. We arrived at the hospital at 9:00 A.M. to find that Dad was still asleep and restrained, the nurse’s name was not on the board, and Dad’s feeding tube was empty. Two out of three of these situations were unacceptable. I went to the nurse’s station to find out who his nurse was and to let them know that his tube feed bottle was empty. A nurse entered the room with a fresh bottle of Nepro, changed out his tubing, and replaced the empty bottle. The nurse also told me that Dad’s nurse was Nicole, who finally showed up at 9:15 A.M. and introduced herself. August 10. We arrived at 7:40 A.M. and noticed that Dad was already on dialysis. Before we arrived, they had drawn blood and ran an

August 10. We arrived at 7:40 A.M. and noticed that Dad was already on dialysis. Before we arrived, they had drawn blood and ran an

August 5, 2015. When Mom and I arrived this morning, Dr. Brett Ambroson, the resident, was finishing up his morning assessment of Dad’s current status. We were pleased to learn that the vomiting episodes from the previous day had stopped. Dr. Ambroson also noted that Dad would now move his extremities when prompted by him or the other care providers. When I asked about Dad’s WBC count, the doctor said that it was down slightly from yesterday. I wasn’t thrilled with the very slight decrease, but at least the steady upward trend had been arrested. While speaking with Dr. Ambroson, Lucy and Cheryl, the dialysis nurse and her aide, prepared Dad for another eight-hour session.

August 5, 2015. When Mom and I arrived this morning, Dr. Brett Ambroson, the resident, was finishing up his morning assessment of Dad’s current status. We were pleased to learn that the vomiting episodes from the previous day had stopped. Dr. Ambroson also noted that Dad would now move his extremities when prompted by him or the other care providers. When I asked about Dad’s WBC count, the doctor said that it was down slightly from yesterday. I wasn’t thrilled with the very slight decrease, but at least the steady upward trend had been arrested. While speaking with Dr. Ambroson, Lucy and Cheryl, the dialysis nurse and her aide, prepared Dad for another eight-hour session. I returned to the hospital at 6:30 P.M., armed with a couple of small bottles of water. The physical therapist had told me that lifting the bottles while in bed would be good exercise for Dad. Unfortunately, he wouldn’t touch the bottles. I tried talking with him and shared some of his improved lab results with him, but nothing helped. I even tried to make a deal with him and told him that if he would exercise even a little, I would eat peas, which I detest. I still haven’t had any reason to eat peas.

I returned to the hospital at 6:30 P.M., armed with a couple of small bottles of water. The physical therapist had told me that lifting the bottles while in bed would be good exercise for Dad. Unfortunately, he wouldn’t touch the bottles. I tried talking with him and shared some of his improved lab results with him, but nothing helped. I even tried to make a deal with him and told him that if he would exercise even a little, I would eat peas, which I detest. I still haven’t had any reason to eat peas. August 3, 2015. It had now been 90 days since Dad first entered the hospital for his seven-to-ten day stay. When Mom and I arrived at 7:45 A.M., Dad’s room was a hubbub of activity. Dr. Phan, the nephrology resident, was assessing him and Emily, his nurse, was exercising his arms and legs. But the first thing that we noticed was Dad’s bed. Yesterday, Dr. Jimenez had told Dad’s nurse that he wanted to see Dad’s bed raised to a more upright position. I had envisioned that the angle of his bed would change from 30 to 75 degrees. What we saw instead was a bed that had morphed into a chair. It played music, automatically adjusted to specific angles, and could change into a chair. Was there anything that this bed couldn’t do?

August 3, 2015. It had now been 90 days since Dad first entered the hospital for his seven-to-ten day stay. When Mom and I arrived at 7:45 A.M., Dad’s room was a hubbub of activity. Dr. Phan, the nephrology resident, was assessing him and Emily, his nurse, was exercising his arms and legs. But the first thing that we noticed was Dad’s bed. Yesterday, Dr. Jimenez had told Dad’s nurse that he wanted to see Dad’s bed raised to a more upright position. I had envisioned that the angle of his bed would change from 30 to 75 degrees. What we saw instead was a bed that had morphed into a chair. It played music, automatically adjusted to specific angles, and could change into a chair. Was there anything that this bed couldn’t do? While Mom and I were at home for dinner, I printed out some recent photos of Dad with the family. I wanted the hospital personnel to see him as more than the sick man that they attended in that hospital bed. He hadn’t entered the hospital as some sickly old man, and I wanted them to have a sense of who he was just a few months earlier. After dinner, Mom and I returned to the hospital around 6:50 P.M. and learned that Dustin was Dad’s nurse. I wasn’t impressed with this nurse, and I wasn’t thrilled to see him again.

While Mom and I were at home for dinner, I printed out some recent photos of Dad with the family. I wanted the hospital personnel to see him as more than the sick man that they attended in that hospital bed. He hadn’t entered the hospital as some sickly old man, and I wanted them to have a sense of who he was just a few months earlier. After dinner, Mom and I returned to the hospital around 6:50 P.M. and learned that Dustin was Dad’s nurse. I wasn’t impressed with this nurse, and I wasn’t thrilled to see him again. I had never heard about procalcitonin (PCT) until today, when Dr. Jimenez mentioned that Dad’s current level was 48—down from 64. As soon as the doctor left the room, I whipped out my iPad and searched the internet for information about PCT. From what I read, a PCT level greater than 10 indicated a “high likelihood of severe sepsis or septic shock.” You didn’t have to be a PhD to know that a PCT level of 48 was pretty bad.

I had never heard about procalcitonin (PCT) until today, when Dr. Jimenez mentioned that Dad’s current level was 48—down from 64. As soon as the doctor left the room, I whipped out my iPad and searched the internet for information about PCT. From what I read, a PCT level greater than 10 indicated a “high likelihood of severe sepsis or septic shock.” You didn’t have to be a PhD to know that a PCT level of 48 was pretty bad. When Dr. Jimenez and his entourage entered the room, he said that Dad was “one tough guy.” He said something about an albumin transfusion (protein) to help with absorption, but I was too excited to remember everything that he said. Mom and I knew that Dad was still in the woods, but we felt that he had finally found the path out. Before the doctor left, he told Melissa, the nurse, that he wanted the bed raised to more of a sitting position. This day also marked the first day since my father’s return that we didn’t hear something about his grave prognosis.

When Dr. Jimenez and his entourage entered the room, he said that Dad was “one tough guy.” He said something about an albumin transfusion (protein) to help with absorption, but I was too excited to remember everything that he said. Mom and I knew that Dad was still in the woods, but we felt that he had finally found the path out. Before the doctor left, he told Melissa, the nurse, that he wanted the bed raised to more of a sitting position. This day also marked the first day since my father’s return that we didn’t hear something about his grave prognosis. Shortly after 10:00 A.M., we met

Shortly after 10:00 A.M., we met  When Dad was transferred from the CCH to Memorial, his flowers could not come with him. Cut flowers and plants are not permitted in the ICU. I had been thinking about it for a couple of days, and I was now determined to brighten up Dad’s room. After lunch, I cleaned the vase that had held his sunflower arrangement, took it back to

When Dad was transferred from the CCH to Memorial, his flowers could not come with him. Cut flowers and plants are not permitted in the ICU. I had been thinking about it for a couple of days, and I was now determined to brighten up Dad’s room. After lunch, I cleaned the vase that had held his sunflower arrangement, took it back to  July 28, 2015. Six days since Dad returned to

July 28, 2015. Six days since Dad returned to  The big surprise of the week occurred right after Dr. White left Dad’s room. During the procession of residents and the attending physician, a woman kept appearing in the doorway, and would then leave. When the room was finally empty of providers, she entered Dad’s room and introduced herself as Aimee from the Patient Relations department. She told us that a hospital employee had contacted her office about Dad, and suggested that she meet with us about the events that led to his return to Memorial. I pulled out my iPad of notes and shared our concerns about some of our interactions with one of the CCH doctors. Aimee told us that they would investigate our complaint and get back to us in 30 days. I assured her that although we had complaints about one person, for the most part, we were pleased with the level of care that Dad had received from his providers. When she left, Mom and I were stunned and kept trying to guess who contacted Aimee’s office.

The big surprise of the week occurred right after Dr. White left Dad’s room. During the procession of residents and the attending physician, a woman kept appearing in the doorway, and would then leave. When the room was finally empty of providers, she entered Dad’s room and introduced herself as Aimee from the Patient Relations department. She told us that a hospital employee had contacted her office about Dad, and suggested that she meet with us about the events that led to his return to Memorial. I pulled out my iPad of notes and shared our concerns about some of our interactions with one of the CCH doctors. Aimee told us that they would investigate our complaint and get back to us in 30 days. I assured her that although we had complaints about one person, for the most part, we were pleased with the level of care that Dad had received from his providers. When she left, Mom and I were stunned and kept trying to guess who contacted Aimee’s office. His pulse was running in the 130s again, and his oxygen saturation levels were low. To compensate for the low oxygen levels, the respiratory therapist increased his oxygen levels on the ventilator to 60%. A few minutes later, the ventilator started alarming, which prompted the nurse to page the respiratory therapist. Evidently, one piece of the ventilator was cross-threaded, which was what caused the system to alarm. The alarms were starting to drive us crazy and I could swear that I could hear them when we were away from the hospital.

His pulse was running in the 130s again, and his oxygen saturation levels were low. To compensate for the low oxygen levels, the respiratory therapist increased his oxygen levels on the ventilator to 60%. A few minutes later, the ventilator started alarming, which prompted the nurse to page the respiratory therapist. Evidently, one piece of the ventilator was cross-threaded, which was what caused the system to alarm. The alarms were starting to drive us crazy and I could swear that I could hear them when we were away from the hospital. When Dr. White and his band of providers arrived outside of Dad’s room, I heard comments about Dad being

When Dr. White and his band of providers arrived outside of Dad’s room, I heard comments about Dad being  Shortly before 4:00 P.M., I was presented with a

Shortly before 4:00 P.M., I was presented with a  Carlos, the dialysis nurse, arrived at 8:15 A.M. and proceeded to prepare Dad for dialysis. At the same time, Dr. Fernandez, one of the

Carlos, the dialysis nurse, arrived at 8:15 A.M. and proceeded to prepare Dad for dialysis. At the same time, Dr. Fernandez, one of the  At 2:15 P.M., the hematology team arrived. Because Dad’s lab work showed that he had

At 2:15 P.M., the hematology team arrived. Because Dad’s lab work showed that he had  Dad’s oxygen levels had been fair, and when Nikita, the respiratory therapist arrived, she increased his oxygen level on the ventilator from 40% to 50%. As she adjusted the ventilator settings, she said that she’d probably decrease the levels back to 40% later in the day.

Dad’s oxygen levels had been fair, and when Nikita, the respiratory therapist arrived, she increased his oxygen level on the ventilator from 40% to 50%. As she adjusted the ventilator settings, she said that she’d probably decrease the levels back to 40% later in the day. July 26, 2015. Mom and I arrived at the hospital shortly after 8:00 A.M.; I looked at Dad, and then over to his IVs. Amazingly, Dad’s night nurse, Tyler, had been able to wean Dad down to one

July 26, 2015. Mom and I arrived at the hospital shortly after 8:00 A.M.; I looked at Dad, and then over to his IVs. Amazingly, Dad’s night nurse, Tyler, had been able to wean Dad down to one  When Dr. White arrived, he acknowledged that while there had been some clinical improvement in my dad’s condition, Dad was still critically ill and his mental status was not improving. To ensure that Dad hadn’t suffered a stroke or a bleed, he planned to order a CT scan. Dr. White restated his concern about Dad’s toes and thought that he probably would lose at least one toe.

When Dr. White arrived, he acknowledged that while there had been some clinical improvement in my dad’s condition, Dad was still critically ill and his mental status was not improving. To ensure that Dad hadn’t suffered a stroke or a bleed, he planned to order a CT scan. Dr. White restated his concern about Dad’s toes and thought that he probably would lose at least one toe. While Mom, Stan, and I were at home for lunch, I decided I would try some music therapy with Dad.

While Mom, Stan, and I were at home for lunch, I decided I would try some music therapy with Dad.