August 1, 2015. When Mom and I arrived at the hospital at 7:45 A.M., the respiratory therapist was administering oral care to Dad. Shortly after she left, the nephrology fellow stopped by to check Dad’s status to determine whether he would need dialysis. He noted that Dad’s feet were very swollen, which prompted Shannon, his nurse, to remove his leg massagers, which had been present since his readmittance.

I had never heard about procalcitonin (PCT) until today, when Dr. Jimenez mentioned that Dad’s current level was 48—down from 64. As soon as the doctor left the room, I whipped out my iPad and searched the internet for information about PCT. From what I read, a PCT level greater than 10 indicated a “high likelihood of severe sepsis or septic shock.” You didn’t have to be a PhD to know that a PCT level of 48 was pretty bad.

I had never heard about procalcitonin (PCT) until today, when Dr. Jimenez mentioned that Dad’s current level was 48—down from 64. As soon as the doctor left the room, I whipped out my iPad and searched the internet for information about PCT. From what I read, a PCT level greater than 10 indicated a “high likelihood of severe sepsis or septic shock.” You didn’t have to be a PhD to know that a PCT level of 48 was pretty bad.

Dad’s blood pressure was all over the place, and Shannon had a tough time finding the sweet spot with Dad’s vasopressor dosages. A couple of times, his blood pressure skyrocketed, and then after the vasopressors were reduced, it would plummet. It seemed like the monitor would never quit alarming.

Stan left Houston earlier this morning, arriving at the hospital around 11:20 A.M. We spoke on the phone every night, but I always looked forward to seeing him arrive for his weekend visits.

Something about the sound of Dad’s breathing bothered me. To me, it sounded like he was breathing under water. We called for the nurse, who then called the respiratory therapist. It seemed that Dad’s trach tube had a leak. After a couple of visits, the respiratory therapist was able to patch it.

Dad seemed to be becoming slightly more responsive. During the past few days, Dad had been oblivious to anything that was done to him. Today, I stayed by his side during some of the daily procedures and held his hand, and he kept a vice grip on my hand during a couple of the visits from therapists. I couldn’t tell whether he was in pain or scared, but he was somewhat aware. He still wouldn’t follow verbal commands, but he was withdrawing to pain in his feet. I still cringed whenever they inflicted pain to test his responsiveness.

During one of his long naps, I reviewed the copious notes that I had been keeping about Dad’s hospital stay, and I composed a letter to Amiee McIlwain in Patient Relations about the nurses who had provided exemplary care for Dad. We had voiced several complaints during her visit with us and Mom and I wanted her to know that we weren’t just complainers. We knew good care givers when we saw them, and we were pleased to acknowledge them.

As I was preparing to leave for dinner, Dad’s blood pressure resumed its roller-coaster behavior. Shannon had little trouble controlling it, and I left at 4:30 P.M. when I felt that Dad was somewhat stable.

When Mom and I returned to the hospital after dinner, Dad was resting comfortably. He was still receiving a vasopressor, but the dosage was minimal. We met with Rebecca, Dad’s night nurse, and stayed until she ran through her initial assessment of him. She tried her best to perform a neurological assessment, but he was nonresponsive. After he had seemed somewhat responsive earlier in the day, seeing him this way was disheartening.

Mom and I went home shortly before 8:00 P.M. We were familiar with Rebecca and we felt that Dad would have a reasonably good night. My cell phone number was written on the dry-erase board in Dad’s room. Every night as I left the hospital, I hoped that they would have no reason to use it.

August 2. Mom and I arrived to the hospital earlier than normal for a Sunday, which was fortunate because Dr. Jimenez also stopped by early. Eavesdropping was my strategy for obtaining information. This morning, while standing on the threshold of Dad’s room, I overheard an interesting conversation in the hall between the good doctor and one of the residents. After the resident reviewed Dad’s lab work, particularly the PCT count, he offered a pretty poor prognosis for my father. The doctor told him that although Dad’s PCT was still very high, he had to look at the trend, and in the period of two days, my father’s PCT count had dropped from 64 to 38. Dr. Jimenez then said, “This guy is turning around.”

When Dr. Jimenez and his entourage entered the room, he said that Dad was “one tough guy.” He said something about an albumin transfusion (protein) to help with absorption, but I was too excited to remember everything that he said. Mom and I knew that Dad was still in the woods, but we felt that he had finally found the path out. Before the doctor left, he told Melissa, the nurse, that he wanted the bed raised to more of a sitting position. This day also marked the first day since my father’s return that we didn’t hear something about his grave prognosis.

When Dr. Jimenez and his entourage entered the room, he said that Dad was “one tough guy.” He said something about an albumin transfusion (protein) to help with absorption, but I was too excited to remember everything that he said. Mom and I knew that Dad was still in the woods, but we felt that he had finally found the path out. Before the doctor left, he told Melissa, the nurse, that he wanted the bed raised to more of a sitting position. This day also marked the first day since my father’s return that we didn’t hear something about his grave prognosis.

Melissa tried lowering Dad’s already-low dosage of Levophed, but his blood pressure dropped sharply shortly after she left the room. After I called for her, she struggled to raise his blood pressure to a minimally-acceptable level. By the time that Stan arrived at 10:00 A.M., Dad was stable again, but his Levophed dosage was back to where it was when we had arrived.

While Mom and I were at home having lunch with Stan, Pastor Don stopped by the hospital to see Dad and say a prayer; we were now big on prayer. When Mom and I returned to the hospital at 1:30 P.M., Stan headed back to Houston. Shortly after we returned to the hospital, the respiratory therapist told us that they were going to try to move Dad from CPAP to BiPAP respiratory support. It seemed like there was suddenly a flurry of positive activity around Dad, and it felt good.

The downside of Dad’s improving mentation was his increased agitation. He repeatedly lifted his arms and pointed, and then looked concerned. We were pretty certain that he was hallucinating. Because he was unable to communicate, we couldn’t tell what he was seeing or thinking. We spoke with the nurse about his apparent hallucinations, and after consulting with the doctor, she increased his dosage of Fentanyl to help him sleep more. We didn’t like the idea of keeping him stoned, but we didn’t want him to decannulate himself or pull out his feeding tube.

When we returned at the hospital after dinner, we met Maggie, Dad’s night nurse. She was a high-energy woman, and I liked her immediately. She mentioned that she had helped Rebecca bathe Dad the previous night. Before we left, she stretched his arms and feet, something that I would try to remember to do for him in the days following.

Dad was still receiving a minimal dosage of Levophed, and his blood pressure and other vitals seemed pretty stable. He woke up a couple of times before we left and seemed to be seeing more hallucinations.

Maggie was assigned only one other patient, and we left at 8:00 P.M., feeling relatively positive that he would have a good night, unless he woke up to more hallucinations.

July 26, 2015. Mom and I arrived at the hospital shortly after 8:00 A.M.; I looked at Dad, and then over to his IVs. Amazingly, Dad’s night nurse, Tyler, had been able to wean Dad down to one

July 26, 2015. Mom and I arrived at the hospital shortly after 8:00 A.M.; I looked at Dad, and then over to his IVs. Amazingly, Dad’s night nurse, Tyler, had been able to wean Dad down to one  When Dr. White arrived, he acknowledged that while there had been some clinical improvement in my dad’s condition, Dad was still critically ill and his mental status was not improving. To ensure that Dad hadn’t suffered a stroke or a bleed, he planned to order a CT scan. Dr. White restated his concern about Dad’s toes and thought that he probably would lose at least one toe.

When Dr. White arrived, he acknowledged that while there had been some clinical improvement in my dad’s condition, Dad was still critically ill and his mental status was not improving. To ensure that Dad hadn’t suffered a stroke or a bleed, he planned to order a CT scan. Dr. White restated his concern about Dad’s toes and thought that he probably would lose at least one toe. While Mom, Stan, and I were at home for lunch, I decided I would try some music therapy with Dad.

While Mom, Stan, and I were at home for lunch, I decided I would try some music therapy with Dad.

For the past few weeks, Mom and I had been unable to unlock the front door with the house key. Stan had sprayed graphite into the lock and that remedy had worked for a couple of weeks, but we were now back to square one. We didn’t have the time or inclination to fix it, so we just accessed the house from other doors. The front door lock was just an example of life’s little inconveniences that didn’t seem all that important at the time.

For the past few weeks, Mom and I had been unable to unlock the front door with the house key. Stan had sprayed graphite into the lock and that remedy had worked for a couple of weeks, but we were now back to square one. We didn’t have the time or inclination to fix it, so we just accessed the house from other doors. The front door lock was just an example of life’s little inconveniences that didn’t seem all that important at the time. July 15. During dialysis, Dad told the nephrologist that he wanted to go home. The doctor told him that to be declared dialysis dependent (with End Stage Renal Disease), he had to be hospitalized and on dialysis for a total of 12 weeks. Although Mom and I had heard this news a few days ago, it was new news for Dad and prompted him to start asking questions about billing. The doctor contacted Marty Edens, the social worker, who dropped by to answer his questions. Marty couldn’t answer his specific billing questions, but she was familiar with Medicare and some of Dad’s situation. Dad told Marty that he “can’t imagine being here for six more weeks.” He repeatedly told her that he “

July 15. During dialysis, Dad told the nephrologist that he wanted to go home. The doctor told him that to be declared dialysis dependent (with End Stage Renal Disease), he had to be hospitalized and on dialysis for a total of 12 weeks. Although Mom and I had heard this news a few days ago, it was new news for Dad and prompted him to start asking questions about billing. The doctor contacted Marty Edens, the social worker, who dropped by to answer his questions. Marty couldn’t answer his specific billing questions, but she was familiar with Medicare and some of Dad’s situation. Dad told Marty that he “can’t imagine being here for six more weeks.” He repeatedly told her that he “

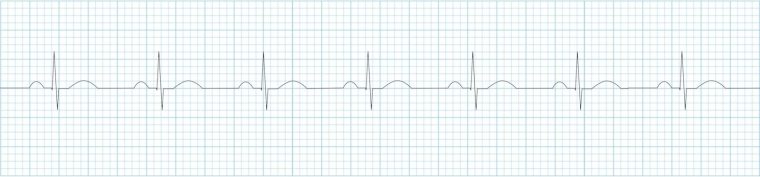

Dad’s cardiologist stopped by and performed a

Dad’s cardiologist stopped by and performed a  During my five days in Temple I had been living in a sort of surreal and parallel universe. When I arrived on May 15, I had assumed that my father’s discharge was imminent. My big unknown was about what was in store for my mother. I had not anticipated that my mother would be discharged first. Now, in addition to figuring out how to care for my recently independent and active parents, I had to start thinking about my job and living away from my husband. It was a daunting juggling act—one I hoped would be over soon.

During my five days in Temple I had been living in a sort of surreal and parallel universe. When I arrived on May 15, I had assumed that my father’s discharge was imminent. My big unknown was about what was in store for my mother. I had not anticipated that my mother would be discharged first. Now, in addition to figuring out how to care for my recently independent and active parents, I had to start thinking about my job and living away from my husband. It was a daunting juggling act—one I hoped would be over soon.