August 29, 2015. Dad’s day started around 5:00 A.M. when he was visited by Mary, a wound care nurse. The CCH wound care nurses not only tended to wounds, which you might expect, they also trimmed nails and would give Dad a shave. Neither Dad nor Mom was a fan of facial hair, so they both felt better after he received a spruce up from wound-care nurses.

When Mom and I arrived at the CCH at 7:45 A.M., Dad was sleeping. A few minutes later, the respiratory therapist woke him, finished his breathing treatment, and administered his oral care. While she was finishing her session with Dad, Dr. White arrived. He and I stepped out of the room and discussed a treatment plan for Dad that would enable him to transfer from the CCH to a skilled nursing facility (SNiF) before his hospitalization benefits expired. If we could get him into a SNiF, he could receive up to 100 days for rehabilitation therapies. When I met with Marty yesterday, she and I agreed that we would like to see him leave the CCH within a couple weeks so that he wouldn’t use up all of his lifetime reserve days of Medicare coverage.

When Mom and I arrived at the CCH at 7:45 A.M., Dad was sleeping. A few minutes later, the respiratory therapist woke him, finished his breathing treatment, and administered his oral care. While she was finishing her session with Dad, Dr. White arrived. He and I stepped out of the room and discussed a treatment plan for Dad that would enable him to transfer from the CCH to a skilled nursing facility (SNiF) before his hospitalization benefits expired. If we could get him into a SNiF, he could receive up to 100 days for rehabilitation therapies. When I met with Marty yesterday, she and I agreed that we would like to see him leave the CCH within a couple weeks so that he wouldn’t use up all of his lifetime reserve days of Medicare coverage.

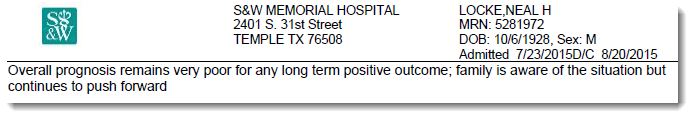

Dr. White thought that Dad had some challenges that could prevent him from transferring to a SNiF. The doctor thought that the feeding tube would be a problem, along with Dad’s mentation and diminished strength. He also suspected that the trach tube might be another obstacle, but he wasn’t sure. He did say that based on the CT scan from yesterday afternoon, Dad’s lung condition was improving.

The doctor said that he could start the process of removing Dad’s trach tube, but he’d been moving cautiously in that regard in case they needed to intubate Dad again. I asked if Dad could start receiving swallow therapy and he said that he’d request a swallow evaluation on Monday. Dr. White said that he’d have Marty give us a list of SNiFs so that we could contact some of them to get an idea about the goals we needed to meet to transfer Dad by Oct. 1st. I told him that I’d like to aim a little higher and get him transferred sooner. He also said that Dad’s nights had been uneventful since he got out of bed a few days earlier. He also said that he would meet with Rachel, the nurse practitioner, to see if she could offer any insight into conditions that could prevent him from being admitted to a SNiF.

When I returned to his room, Dad asked to see his list of exercises. When I couldn’t lay my hands on it, he became somewhat annoyed and agitated that it was lost. I finally got him to calm down when I assured him that I’d help him redo the list.

He grimaced a lot during the morning and finally told us that his shoulder was hurting him a lot. We called for Christine, the nurse, and requested some pain medicine. A few minutes after she gave him the meds, he started complaining about sharp pains in his head. After conferring with the nurse, we suspected that the pain in his shoulder was radiating to his head. After the pain medicine took effect, he stopped complaining about pain.

Kevin from x-ray stopped by around 10:00 A.M to x-ray Dad’s shoulder. While Mom and I sat in the waiting room, I told her about my conversation with Dr. White. She didn’t want Dad to go to a SNiF, and said that she and Dad had promised each other that they would not institutionalize each other. I hadn’t expected this response. A good friend of hers had checked herself into a SNiF during her convalescence from hip surgery. I had no intention of institutionalizing Dad, but we were running out of hospitalization benefits and had to find a place where he could complete his recovery. I told her that not using a SNiF would mean that she would have to hire caregivers to come to the house. She probably would not be able to leave him alone if he was at the house. I was also pretty sure that Medicare would not cover this expense. She said that she didn’t care and would be willing to do what was necessary to keep him out of a nursing home. We dropped the subject for the time being when we returned to Dad’s room.

Dad was a lot more comfortable when the bed extension was on his bed. Unfortunately, when the extension was on the bed, the bed wouldn’t fit into the elevator, so most of the time, the extension sat in the corner of the room. Because the weekend afforded him a couple days without elevators, Christine attached the bed extension.

Dad fell asleep pretty fast when the pain meds kicked in, which seemed like a good time for Mom and me to slip out for lunch.

When we returned after lunch, Dad was lying diagonally in the bed. After Christine got him resituated, Dad and I spent much of the afternoon redoing his exercise routine. I had to talk him down from some of the exercises that he used to do in boot camp some 65 years ago. I hoped that he would be as gung-ho at execution as he was during planning. So far, the physical therapist could barely get him to stand up on the side of the bed.

The three of us watched some of the golf tournament in the afternoon, but Dad had received more pain medicine and he kept drifting off to sleep during our conversations. After one such dozing off at 4:45 P.M., Mom and I went home.

Mom and I continued our tense discussions about moving Dad from the CCH to Marlandwood West, which was a SNiF in the neighbor that, on paper, seemed like a great option for him. Mom still wasn’t convinced, and she was also very concerned about the upcoming week because Dr. Anderson would be returning as the attending physician. It was probably just a freakish coincidence, but nothing seemed to go well for Dad when Dr. Anderson was there. With all that we had going on, I decided to stay in Temple a little longer. Instead of going home on Sunday, I agreed to stay through 4:00 P.M. on Monday. In addition to seeing Dr. Anderson, I would try to stop by Marlandwood with Mom and check out the facility. At this point, we had been arguing about what we envisioned the environment to be like. We needed to see it first-hand.

While Mom and I were at home discussing rehab options, back at the CCH, Dad was attempting to get out of bed so that he could use the bathroom. Luckily, Andrea, the night nurse, intercepted his escape and convinced him to remain in bed. Fortunately, Dad stayed in bed for the remainder of the night.

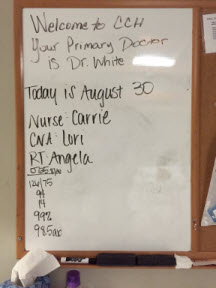

August 30. Every morning that he was in the hospital, Dad received a briefing of sorts from the nurse about the importance of staying in bed and using the call light when he needed assistance. From what I had witnessed so far, Dad had not taken these daily briefings to heart. Truth be told, between his delirium and some of his meds, I doubted that he could remember these chats with the nurses for more than a few minutes.

Mom and I arrived at the CCH at 9:05 A.M. to find that Dad was still sleeping. We learned that Dr. White was making his rounds, but he had already been to Dad’s room. We woke Dad and eventually convinced him to wear his hearing aids and wear glasses. Glasses and hearing aids might not seem like a big deal, but wearing them wasn’t always a given with him. Stan arrived at 10:00 A.M. to spell me and Mom while we attended church.

The church service lasted 15 minutes longer than usual, so we didn’t arrive home until 12:30 P.M. We were surprised that Stan wasn’t already there, but he arrived shortly after we arrived. Dad had been asking about the finances, but they were on his computer, which I had disconnected so that I could work from his desk. When we finished lunch, Stan hooked up Dad’s computer again in case he asked me to look up some financial information for him.

After saying goodbye to Stan, Mom and I returned to the CCH at 2:00 P.M. When we entered Dad’s room, we found that Angela was in his room and Dad was partway out of the bed. I tried again to see if we could raise the fourth rail but to no avail.

We had not been able to speak with the doctor today. When we asked Carrie if she could find him for us, she said that Dr. White had left the building. We had seen him walk by several times, so either she was misinformed or he had left and had subsequently returned. Regardless, we never saw him again.

For most of the afternoon, Dad slept while Mom and I watched the Barclay’s golf tournament. I hated that he slept so much, but at least we weren’t arguing about the importance of staying in bed or why he couldn’t go home. Mom and I finally left for home shortly after 4:30 P.M.

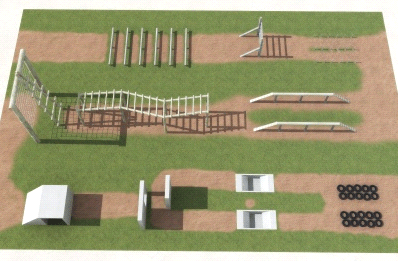

August 31. Mom had a doctor’s appointment this morning, and when she returned, she and I drove to Marlandwood, the SNiF that was located less than three miles from my parents’ house. Like many nursing facilities, it housed rehab patients who were building back their strength so that they could safely return home. Half of the facility was devoted to permanent residents.

While at the Marlandwood facility, Mom and I visited with Stacy and Colleen, representative of the facility, about moving Dad. We weren’t wild about the semi-private rooms, but we were impressed with the respiratory therapist and the PT and OT personnel. They seemed devoted to building up their rehab patients for their safe return home and they had no qualms about any of Dad’s conditions that we raised. Mom and I were very optimistic about Dad’s situation until we returned to the CCH and talked with Rachel, the nurse practitioner. According to her, Dad could not receive offsite dialysis with a trach unless he could remove his own secretions. She also said that he would need to be able to change out his trach, should a problem arise during dialysis. She reminded me that having the four rails up on the bed was considered restraint, and a SNiF would not accept him if he had been restrained. It was a terrible conversation. I know that everyone loved Rachel, but she had never offered up anything but obstacles. We never heard a single suggestion from her to help us in our plight.

At 2:55 P.M., Holly stopped by for a bedside swallow assessment. She came armed with ice, grape juice, and pudding, but Dad totally refused to participate. I couldn’t take it for another minute. After trying unsuccessfully to get him to exert any effort, I yelled at him and left the building. By 3:05 P.M. I was in my car and on my way home. Between the numerous obstacles and his inability to overcome them, I was frustrated to the breaking point and I felt like I was about to explode. I stopped by the house to pick up my computer and drove home–fuming all the way. Once again, it seemed like Dad’s biggest obstacle was Dad.

At 2:55 P.M., Holly stopped by for a bedside swallow assessment. She came armed with ice, grape juice, and pudding, but Dad totally refused to participate. I couldn’t take it for another minute. After trying unsuccessfully to get him to exert any effort, I yelled at him and left the building. By 3:05 P.M. I was in my car and on my way home. Between the numerous obstacles and his inability to overcome them, I was frustrated to the breaking point and I felt like I was about to explode. I stopped by the house to pick up my computer and drove home–fuming all the way. Once again, it seemed like Dad’s biggest obstacle was Dad.

Mom had been encouraged

Mom had been encouraged

With the exception of a couple of golf tournaments, Dad hadn’t been watching any television since May 6. To catch him up on the latest political happenings, Mom brought him the Newsweek magazine that had Donald Trump’s picture on the cover. At the time, Mr. Trump still didn’t seem like he’d make it to the general election, let alone the White House.

With the exception of a couple of golf tournaments, Dad hadn’t been watching any television since May 6. To catch him up on the latest political happenings, Mom brought him the Newsweek magazine that had Donald Trump’s picture on the cover. At the time, Mr. Trump still didn’t seem like he’d make it to the general election, let alone the White House. Today was dialysis day, so Mom and I spent the morning at home doing chores and picked 284 tomatoes from the vegetable garden. We had picked so many tomatoes this summer that Mom and I were eating tomato sandwiches every day—sometimes twice a day. We arrived at the CCH at 12:30 P.M. and encountered

Today was dialysis day, so Mom and I spent the morning at home doing chores and picked 284 tomatoes from the vegetable garden. We had picked so many tomatoes this summer that Mom and I were eating tomato sandwiches every day—sometimes twice a day. We arrived at the CCH at 12:30 P.M. and encountered  August 23. Sundays at the CCH were pretty uneventful. There was no dialysis or therapies and you didn’t see the doctors after the morning rounds unless there was a problem. You’d think that the parking lot would be full of cars, but the CCH wasn’t teeming with visitors. The place seemed empty, dark, and depressing. The doctors at Memorial had told me on more than one occasion that a primary reason for transferring Dad from the ICU to the CCH was so that he could be exposed to more light. These rooms had small windows and even with all the light on, the rooms still seemed dark.

August 23. Sundays at the CCH were pretty uneventful. There was no dialysis or therapies and you didn’t see the doctors after the morning rounds unless there was a problem. You’d think that the parking lot would be full of cars, but the CCH wasn’t teeming with visitors. The place seemed empty, dark, and depressing. The doctors at Memorial had told me on more than one occasion that a primary reason for transferring Dad from the ICU to the CCH was so that he could be exposed to more light. These rooms had small windows and even with all the light on, the rooms still seemed dark. Pam said that she spoke with the doctors about Dad’s delirium, and they wanted to fully vent him at night and had ordered an extra dose of

Pam said that she spoke with the doctors about Dad’s delirium, and they wanted to fully vent him at night and had ordered an extra dose of  Five minutes later, the EMTs arrived to prepare Dad for the trip back to CCH. Because the cuff was deflated on his trach collar, Dad was able to chat with the EMTs without a speaking valve. He seemed to be in good spirits and didn’t exhibit any agitated behavior. The EMTs’ preparations were finished in less than 30 minutes. As they started pushing Dad’s gurney out of his room, Dawn rushed into the room with Dad’s

Five minutes later, the EMTs arrived to prepare Dad for the trip back to CCH. Because the cuff was deflated on his trach collar, Dad was able to chat with the EMTs without a speaking valve. He seemed to be in good spirits and didn’t exhibit any agitated behavior. The EMTs’ preparations were finished in less than 30 minutes. As they started pushing Dad’s gurney out of his room, Dawn rushed into the room with Dad’s  Dr. Stewart then told me and Mom that he wanted to meet with us in a conference room to consult with us about some of Dad’s future possibilities. He started off this consultation by stating that they considered Dad’s recovery to be one of their best achievements and acknowledged our part in that success. He went on to say that he suspected that if Dad did go home, he could have more episodes of pneumonia. He continued by saying that Dad might never fully develop the ability to swallow, and if he did, he could very likely choke on his food and develop pneumonia again. He went on to say that although Dad might never be able to eat peas and carrots, we should let him eat what he wants, regardless of the consequences. He said that there was a good chance that Dad would go home with a trach tube. After that disheartening meeting with one of our favorite caregivers, Mom and I returned to Dad’s room.

Dr. Stewart then told me and Mom that he wanted to meet with us in a conference room to consult with us about some of Dad’s future possibilities. He started off this consultation by stating that they considered Dad’s recovery to be one of their best achievements and acknowledged our part in that success. He went on to say that he suspected that if Dad did go home, he could have more episodes of pneumonia. He continued by saying that Dad might never fully develop the ability to swallow, and if he did, he could very likely choke on his food and develop pneumonia again. He went on to say that although Dad might never be able to eat peas and carrots, we should let him eat what he wants, regardless of the consequences. He said that there was a good chance that Dad would go home with a trach tube. After that disheartening meeting with one of our favorite caregivers, Mom and I returned to Dad’s room.

August 9, 2015. We arrived at the hospital at 9:00 A.M. to find that Dad was still asleep and restrained, the nurse’s name was not on the board, and Dad’s feeding tube was empty. Two out of three of these situations were unacceptable. I went to the nurse’s station to find out who his nurse was and to let them know that his tube feed bottle was empty. A nurse entered the room with a fresh bottle of Nepro, changed out his tubing, and replaced the empty bottle. The nurse also told me that Dad’s nurse was Nicole, who finally showed up at 9:15 A.M. and introduced herself.

August 9, 2015. We arrived at the hospital at 9:00 A.M. to find that Dad was still asleep and restrained, the nurse’s name was not on the board, and Dad’s feeding tube was empty. Two out of three of these situations were unacceptable. I went to the nurse’s station to find out who his nurse was and to let them know that his tube feed bottle was empty. A nurse entered the room with a fresh bottle of Nepro, changed out his tubing, and replaced the empty bottle. The nurse also told me that Dad’s nurse was Nicole, who finally showed up at 9:15 A.M. and introduced herself. August 10. We arrived at 7:40 A.M. and noticed that Dad was already on dialysis. Before we arrived, they had drawn blood and ran an

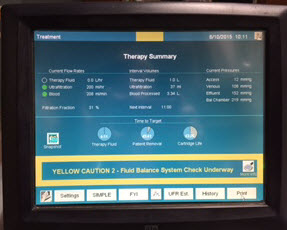

August 10. We arrived at 7:40 A.M. and noticed that Dad was already on dialysis. Before we arrived, they had drawn blood and ran an

August 7, 2015. Mom and I arrived at the hospital at 7:45 A.M. Dad was still receiving CPAP breathing support. We were surprised to see that he was not having dialysis, but we had scarcely put down our purses when Lucy, the dialysis nurse, stopped by and said that she had been told to set up the (traditional) four-hour dialysis session. As she left the room,

August 7, 2015. Mom and I arrived at the hospital at 7:45 A.M. Dad was still receiving CPAP breathing support. We were surprised to see that he was not having dialysis, but we had scarcely put down our purses when Lucy, the dialysis nurse, stopped by and said that she had been told to set up the (traditional) four-hour dialysis session. As she left the room,  August 8. Mom and I arrived at Dad’s room at 6:30 A.M. The room was dark and Dad was still sleeping. Jennifer, his nurse, arrived at 7:30 A.M. and started her morning assessment of Dad. When she was finished, she told us that the night nurse told her that Dad was very agitated during the night. I wasn’t sure what that meant, but it didn’t sound good. On a more positive note, Dad’s WBC count was still trending downward.

August 8. Mom and I arrived at Dad’s room at 6:30 A.M. The room was dark and Dad was still sleeping. Jennifer, his nurse, arrived at 7:30 A.M. and started her morning assessment of Dad. When she was finished, she told us that the night nurse told her that Dad was very agitated during the night. I wasn’t sure what that meant, but it didn’t sound good. On a more positive note, Dad’s WBC count was still trending downward. August 5, 2015. When Mom and I arrived this morning, Dr. Brett Ambroson, the resident, was finishing up his morning assessment of Dad’s current status. We were pleased to learn that the vomiting episodes from the previous day had stopped. Dr. Ambroson also noted that Dad would now move his extremities when prompted by him or the other care providers. When I asked about Dad’s WBC count, the doctor said that it was down slightly from yesterday. I wasn’t thrilled with the very slight decrease, but at least the steady upward trend had been arrested. While speaking with Dr. Ambroson, Lucy and Cheryl, the dialysis nurse and her aide, prepared Dad for another eight-hour session.

August 5, 2015. When Mom and I arrived this morning, Dr. Brett Ambroson, the resident, was finishing up his morning assessment of Dad’s current status. We were pleased to learn that the vomiting episodes from the previous day had stopped. Dr. Ambroson also noted that Dad would now move his extremities when prompted by him or the other care providers. When I asked about Dad’s WBC count, the doctor said that it was down slightly from yesterday. I wasn’t thrilled with the very slight decrease, but at least the steady upward trend had been arrested. While speaking with Dr. Ambroson, Lucy and Cheryl, the dialysis nurse and her aide, prepared Dad for another eight-hour session. I returned to the hospital at 6:30 P.M., armed with a couple of small bottles of water. The physical therapist had told me that lifting the bottles while in bed would be good exercise for Dad. Unfortunately, he wouldn’t touch the bottles. I tried talking with him and shared some of his improved lab results with him, but nothing helped. I even tried to make a deal with him and told him that if he would exercise even a little, I would eat peas, which I detest. I still haven’t had any reason to eat peas.

I returned to the hospital at 6:30 P.M., armed with a couple of small bottles of water. The physical therapist had told me that lifting the bottles while in bed would be good exercise for Dad. Unfortunately, he wouldn’t touch the bottles. I tried talking with him and shared some of his improved lab results with him, but nothing helped. I even tried to make a deal with him and told him that if he would exercise even a little, I would eat peas, which I detest. I still haven’t had any reason to eat peas.