May 18, 2015, was the day that we had been thinking my dad would be discharged from the hospital. Instead, I spent a significant portion of that morning speaking with Dad’s caregivers about his deteriorating condition. In short, he had bacterial pneumonia and severe sepsis with acute organ dysfunction. His medical team was administering several antibiotics, but there was no way in which his cocktail of meds could take care of the amount of infected fluid (pus) in his chest. The doctors recommended that they reopen his chest and wash out the infection. Of course there were some risks, but the alternative was dire. What I didn’t know until May 2016 was that he was also at risk for acute kidney injury.

Dad’s cardiologist stopped by and performed a Transesophageal Echocardiography (TEE). The TEE was necessary to ensure that Dad’s new bovine heart valve wasn’t harboring any infection. I hadn’t met her before and she surprised me when she said, “I didn’t want him to have this procedure. He should be home working in his garden.” My parents never heard that she had had reservations about the more invasive procedure. Lesson learned: regardless of the surgeon’s reputation, have the physician who made the original surgical referral (in this case, the cardiologist) review the surgeon’s recommendation.

Dad’s cardiologist stopped by and performed a Transesophageal Echocardiography (TEE). The TEE was necessary to ensure that Dad’s new bovine heart valve wasn’t harboring any infection. I hadn’t met her before and she surprised me when she said, “I didn’t want him to have this procedure. He should be home working in his garden.” My parents never heard that she had had reservations about the more invasive procedure. Lesson learned: regardless of the surgeon’s reputation, have the physician who made the original surgical referral (in this case, the cardiologist) review the surgeon’s recommendation.

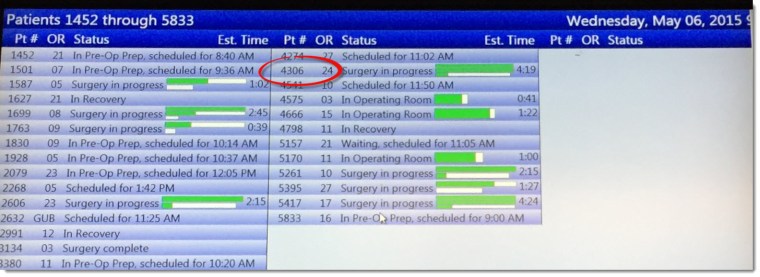

His washout surgery was scheduled for 6:00 P.M. that night, but the surgeon’s earlier procedures had run long, so he opted to wait until the next morning. Although it was a simple procedure, he didn’t want to perform surgery with only a skeleton staff on hand should something go wrong.

On May 19, Rhoda and I arrived early to the hospital. My father’s surgery started at 8:00 A.M., and I received a call shortly after 9:00 A.M. informing me that the surgery was finished. Around lunchtime, we received our first visit from Pastor Don, a pastor from my parents’ church. Before he saw my father, Don visited with my mother for a few minutes before her discharge.

During Mom’s discharge, I learned that she could not be alone or drive for at least 30 days, at which time she would undergo a neurological assessment. I was glad that she was home, although some of our conversations were pretty unsettling. She often could not remember what we asked her or what we or she had just said. To say the least, I was cautiously optimistic about her recovery.

On Wednesday, May 20, my mother and I returned to the hospital to see my father. Rhoda had postponed a trip to Wisconsin to help me, but now she really needed to leave. She stopped by the hospital on her way home. Although my father’s breathing tube had been removed the previous day, speaking was still a little difficult. He managed to call her “a blessing,” when he said good-bye.

Within hours after Rhoda’s departure, Dad was transferred from CTICU back to the fourth floor. We were pleased that he was well enough to transfer, but he wasn’t there very long before it became very apparent that he was extremely disoriented. The fourth-floor charge nurse was more than a little annoyed that he had to assign an aide to my father’s room to ensure that he wouldn’t try to get out of bed or remove some vital tube.

I had had the foresight to take my work computer with me when I hurried to Temple five days earlier. I had been able to do my job in the intervening days even though I was away from my office. Now, however, I needed to return to my home and my office for a couple of days. I also needed to see my physical therapist—I had had surgery myself in March and was still undergoing physical therapy. Lucky for me, my dear husband agreed to come to Temple to relieve me for a couple days. He and I formulated a plan of coverage for Mom until my father was discharged.

On May 21, I worked from my parents’ home until about 8:00 A.M. My mother’s friend Marilyn stopped by to stay with Mom until Stan arrived. Stan and I met in Cameron, Texas, to exchange keys and information. I arrived at my workplace shortly after noon and felt a little guilty for leaving my mother and Stan to contend with my father’s delirium. My sense of guilt was short-lived, however. After being home for an hour or so, I noticed that my house was infested with fleas. Our cats never go outside, but we learned that this year was especially bad for fleas. We frequently employed a pet sitter and assumed that some fleas had hitched a ride with her. At this point Stan and I laughed about this latest situation, wondering what else could go wrong. After flea traps and expensive oral medication for the cats, we finally vanquished the fleas.

During my five days in Temple I had been living in a sort of surreal and parallel universe. When I arrived on May 15, I had assumed that my father’s discharge was imminent. My big unknown was about what was in store for my mother. I had not anticipated that my mother would be discharged first. Now, in addition to figuring out how to care for my recently independent and active parents, I had to start thinking about my job and living away from my husband. It was a daunting juggling act—one I hoped would be over soon.

During my five days in Temple I had been living in a sort of surreal and parallel universe. When I arrived on May 15, I had assumed that my father’s discharge was imminent. My big unknown was about what was in store for my mother. I had not anticipated that my mother would be discharged first. Now, in addition to figuring out how to care for my recently independent and active parents, I had to start thinking about my job and living away from my husband. It was a daunting juggling act—one I hoped would be over soon.

We started in the north tower to see my father. He was sitting up in bed and looked very frail. He seemed to have weakened significantly from the previous evening. He looked up at me and said something that I couldn’t understand. When I asked him what he said, he said, “I think we made a mistake.” I put on my positive face and told him that we couldn’t go back—the surgery was behind us. All we could do was look forward. Rhoda and I visited with him for a more few minutes and then went to see my mother in the hospital’s south tower.

We started in the north tower to see my father. He was sitting up in bed and looked very frail. He seemed to have weakened significantly from the previous evening. He looked up at me and said something that I couldn’t understand. When I asked him what he said, he said, “I think we made a mistake.” I put on my positive face and told him that we couldn’t go back—the surgery was behind us. All we could do was look forward. Rhoda and I visited with him for a more few minutes and then went to see my mother in the hospital’s south tower. Shortly thereafter, a steady stream of doctors, fellows, residents, therapists, aides, and who knows who came through my mother’s door. My California-born mother sometimes has a difficult time understanding some of her native Texas friends. This teaching hospital is teeming with personnel from across the globe, most of whom speak rapidly and are very polite and soft spoken. I finally asked them to let me translate all of their requests. While testing her cognitive impairment, they asked her to spell “world” backwards. After two hours of sleep that followed almost 24 hours awake, I was pretty sure that I couldn’t spell it myself, and would probably fail their tests.

Shortly thereafter, a steady stream of doctors, fellows, residents, therapists, aides, and who knows who came through my mother’s door. My California-born mother sometimes has a difficult time understanding some of her native Texas friends. This teaching hospital is teeming with personnel from across the globe, most of whom speak rapidly and are very polite and soft spoken. I finally asked them to let me translate all of their requests. While testing her cognitive impairment, they asked her to spell “world” backwards. After two hours of sleep that followed almost 24 hours awake, I was pretty sure that I couldn’t spell it myself, and would probably fail their tests. With this new information, I called Scott & White ED again and asked about the status of my mother. Again they told me that they had no such patient. I informed her that neighbors witnessed a Scott & White ambulance drive off with my mother on board. Because my parents’ house was less than five miles from the hospital, I assumed that it was her destination. It was then that she asked me about her symptoms, and as I started to explain, she said, “We have a Jane…” I interrupted her and asked if she was saying that my mother was a Jane Doe. She said that my mother had not been able to identify herself and she was admitted as Trauma Patient Ohio.

With this new information, I called Scott & White ED again and asked about the status of my mother. Again they told me that they had no such patient. I informed her that neighbors witnessed a Scott & White ambulance drive off with my mother on board. Because my parents’ house was less than five miles from the hospital, I assumed that it was her destination. It was then that she asked me about her symptoms, and as I started to explain, she said, “We have a Jane…” I interrupted her and asked if she was saying that my mother was a Jane Doe. She said that my mother had not been able to identify herself and she was admitted as Trauma Patient Ohio.